This country has a bit of a problem with a false sense of security.

So-called revelations have been abounding this week over the extent and nature of some specific acts of torture enacted by the CIA during the Bush administration on behalf of the United States. The torture ranged from breaking limbs to making people pass out to threatening sexual violence against them and their families to threatening death to actually killing them. The country appears to be taking this as news, which itself is kind of news to me, but I guess when I can be chattily accosted by a fellow tournament player about how we “finally got some of those Democrats out” and “it’s crazy how many Socialists are still in government,” it’s pretty clear I have no fingers at all on the pulse of America. His unironic earnestness about what he assumed would be my shared opinion that Mary Landrieu, champion of the Keystone XL Pipeline, Big Energy, and all-around moderate conservative is a Socialist convinced me that I would actually give him a heart attack (he was of a certain vulnerable age) if I declared, honestly, that I am an actual Socialist the likes of which would make Bernie Sanders blush.

No one is really making much of a connection today between the CIA torture stories and the other news that I can only imagine they are trying to displace, namely the matter of the police slaughtering the unarmed (usually Black men) in our society. The connection seems obvious to me, but then the links between various instances of institutional violence always seem pretty clear and traceable from my vantage. We are a people become so obsessed with danger and threats that we have come to see everything as a threat. Or, far more to the point, everyone as a threat. With the increasingly vague excuse of PTSD from 9/11, we trot out our fear like some sort of endless warrant for the abuse and summary execution of anyone we find remotely disconcerting. So quickly forgetting that this is a narrative as old as nations themselves, that fear of the damage from the last war or major attack brought popular support to Hitler’s expansion, Stalin’s purges, Napoleon’s conquests, Robespierre’s terror, and probably every other significant abrogation of rights and life in history. Genocide, ethnic cleansing, and dehumanization are not the products of a society that feels comfortable or stable in itself. They are the products of a society desperate to establish a sense of security through any, preferably rabid, means necessary.

This is an already rutted road in my writing, the discussion of how fear can galvanize evil and how absurd our fears truly are. Even how a different kind of fear motivates our binary lose-lose party system. It’s hard to say how much is a product of American exceptionalism specifically as I have come to believe that no one nation has ever been so good at convincing people of its nobility while spreading iniquity. Or how much of it is just the innate exceptionalism that comes with being a temporal being stuck in a single place in the world, adopting the loyalties and perspectives so tightly bound to the country of one’s origin and rearing. Maybe German exceptionalism and Soviet exceptionalism and French exceptionalism and even Mongol exceptionalism or Hunnic exceptionalism (and certainly Roman exceptionalism) fueled all the atrocities of days gone by. Maybe we aren’t special at all, even in our ability to make ourselves feel more special than the rules of history and power.

But there is perhaps a lighter-hearted metaphor to be found mired in the literal torture and killing our country’s authorities daily enact on the alleged behalf of our safety. One that has also graced the news lately, with head-shaking denotations of the obvious incompetence it implies. Namely, the failure of several institutions to keep passwords in any way safe from hacking, often in the hilarious form of passwords being stored in easy-to-find files named “password”.

You can read all about the story, which was everywhere last week, here, for example.

The problem made most people immediately hit their heads into walls and rush to take part in the bashing of Sony, its IT department, and other gleeful pilings-on so common in our tear-down culture. But no one seemed to raise the issue that seemed more obvious to me, which itself is an issue I’ve been meaning to blog about already anyway. Which is that our current system of Internet security and its attendant passwords are completely unusable by people. They are decently well designed, I suppose, for computers, but as I learn a little bit more each day in the poker world, humans are not computers.

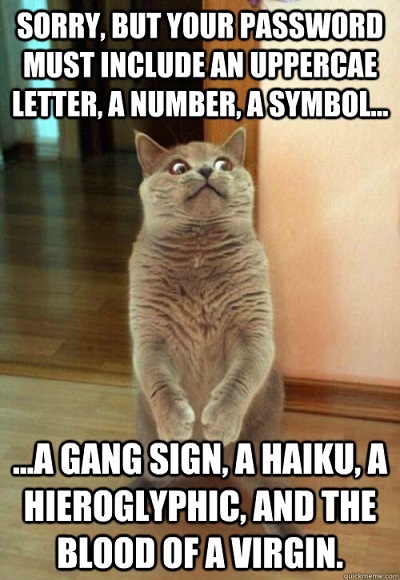

To do most anything on the Internet these days, you need a login for the specific site on which you will be doing that thing. Every site has a different requirement for username protocols, including especially the fact that each login must be unique for that site. And most every site has a different set of requirements for the length, diversity, and criteria of passwords which are handed out. For a clear example, some sites require that a symbol (any key other than a recognizable letter or number) be used at least once in the password, while many others disallow any use of such symbols in passwords. Many sites cap the password length at 12 characters while others require 12 characters as a minimum.

The result is something any even rudimentary Internet user is familiar with – the accumulation of a wide range of relatively diverse passwords. While one could get away with having a few variations on one basic theme as a default password, many stipulations make this practice of streamlining the variance in password requirements impossible. Many sites, especially academic e-mail addresses and an increasing number of more trivial sites, require periodic changing of one’s password and, more perniciously, the banishment of any past precise password after change. Rutgers required this every 3-6 months. Additionally, routine hacks at various retailers and larger threats like the Heartbleed virus render whole swaths of traditionally used username/password combinations void, or at least vulnerable. And thus end-users are constantly barraged by requests or requirements that they change their passwords at various sites while leaving the login screen and username unchanged.

This last bit is important because, in my experience, the only prayer a human actually has of remembering all the various username/password combinations for all their various sites is to have some sort of visual cue or trigger that one associates with that particular page. If I see the logo of a particular bank every time I’m typing some combination, I’m more likely to remember that when logging in as opposed to looking at my GMail login screen. But if I have to change these passwords, then my memory is actually working against me because I have multiple memories of multiple username/password combinations for the same site, meaning that chaos ensues and I end up not remembering my password.

Which wouldn’t be so bad if there weren’t the additional “safety” feature of locking the account to most anything one is attempting to log in to after 3-5 failed attempts at memory. Something that I have triggered at almost every password-change-mandatory site ever, often multiple times. Which then requires the creation of a (wait for it) even newer unique never-before-at-that site password after one has copy/pasted the string of ridiculous alphanumerics generated by the corrective e-mail prompted by the little “Forgot Password” clicky.

There are basically three ways around this conundrum of modern living that do not involve avoiding the creation of Internet logins:

(1) Store a list of passwords somewhere.

(2) Have your browser memorize your passwords and keep them for you.

(3) Never log out.

The problems with all of these should be obvious. (1) is exactly what Sony did, the problem being that the computer was the easiest place to store the passwords since paper is a dying medium. And paper is vulnerable to loss, oversight, destruction, and theft, making a computer seem theoretically more secure, even if it is hackable. Is it more absurd to travel with one’s little piece of paper or to e-mail or text oneself information? All of these are vulnerable. Only one’s memory is truly secure, but that’s faulty, and I guess isn’t secure either if someone is willing to torture the few passwords you remember out of you.

(3) is impractical, though many people try this for a period of time. But both (2) and (3) have the fatal flaw that anyone successfully hacking your machine can not only steal your password, but could immediately change it and log you out, basically locking you out of that account forever. Which may seem far-fetched until you realize that the entire point of having a password system in the first place is to prevent just that outcome. So either they’re hacking you or they aren’t. Either you have to fear your password getting taken over and this leading to some level of identity theft via login, or it’s all overblown, in which case 1234 or password should suffice.

Granted, some sophisticated systems do prompt you via text or some other more direct means than the Internet if you suddenly change your password and your confirmation e-mail address, which is good. But there’s still a lot of damage that can be done pretty quickly there, especially if the account is for your bank holdings or a particularly high-profile Twitter feed. Thus, the entire process of having Internet passwords becomes a quixotic paradox much like voting. The only time it really matters, it can’t possibly matter. Unless you have the most sophisticated memory for passwords ever.

But then I got a password for CounterWallet so I could hold MepCoin, as discussed in my weekly podcast‘s 131st episode. And that was just a string of random, unmemorizable consecutive words that I was told would never be retrievable ever again if lost, stolen, damaged, or forgotten. Which required that I write it down somewhere, which pretty much had to be somewhere electronic to be really permanent in any way, which makes it perfectly vulnerable to hacking. And while I may have a mere one million MepCoin attached to it (real world value: $0 at the moment), people use this to store things like BitCoin and DogeCoin and things that are theoretically supposed to supplant the mighty dollar someday. Which just mandated that I fall into a basic security trap that proves the totally illusory nature of security.

I am tempted here to pivot to a rant against privacy, but passwords may be the last bastion where privacy actually seems to serve a reasonable purpose. In that, without privacy of passwords at a minimum, all bank information for everyone would become public, and we can’t exactly just trust each other. This is the rare instance where a total symmetry of information rewards the worst actors, not the best, and that seems problematic. Yeah, maybe we shouldn’t have private property unequally held at all (told you I’d make Bernie Sanders blush), but we should probably at least have the right to correctly identify our electronic correspondence with others as actually being from us.

In the meantime, it’s pretty clear that our false sense of security is the biggest thing keeping us unsafe. It’s bad enough to torture our alleged enemies into hating us all the more (or for the first time). But to truly believe our own lies about this stuff is as bad as posting our eponymous file called passwords publicly for all to see. We’re just making total fools of ourselves, as anyone outside the self-delusional exceptionalism we embrace can plainly see.