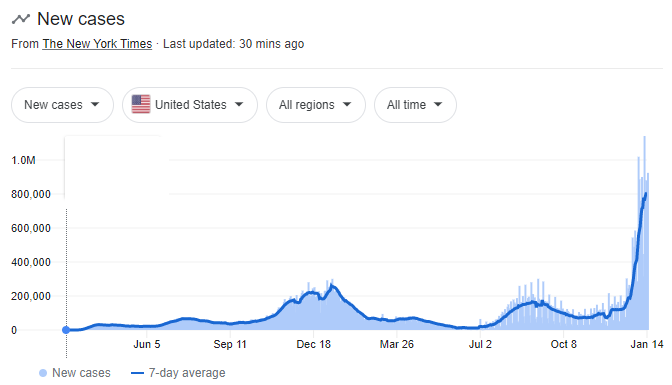

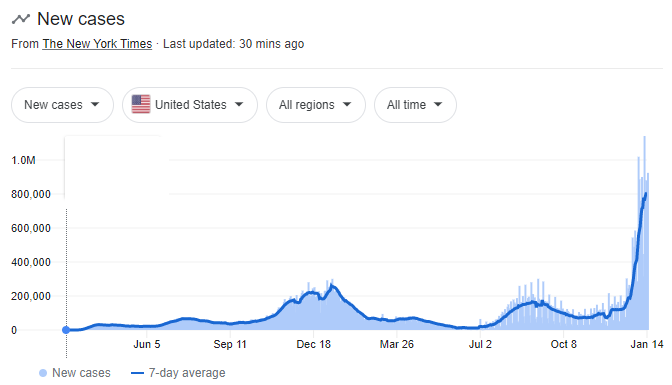

The US has given up trying to fight COVID. Buoyed by the still somewhat speculative notion that the Omicron variant is so weak as to pose a substantially reduced threat, exhausted by nearly two years of half-hearted and poorly-implemented attempts to mitigate the spread of the virus, and above all headed by a government terrified of backlash against another attempt to really limit the disease (and opposed by a recently ousted party who largely questions the existence of said disease at all), America has folded up its tent and raised the white flag. “Let ‘er rip,” the popular phrase du jour goes. We have to wait about a month to see to what extent this translates into “let ’em RIP” and becomes the contemporary equivalent of “let them eat cake,” with equally deadly consequences. After all, hospitalizations tend to lag cases by a couple weeks and deaths lag hospitalizations by a couple more. The fact that we just set an all-time COVID hospitalization record when we’re still barely a fortnight from New Year’s is, of course, a very bad sign.

So what happened? How did we get to a point where the United States of America stared down a deadly threat and concluded the best move was to let it spread and kill as many people as it was going to take? Half a 9/11 a day, a 9/11 a day, a couple 9/11s a day, whatever?

There’s a lot of blame and anger to go around. Let me preface by saying that most of my responses to this situation in most of the places I interact (which, these days, is social media) have been laden in blame and anger. I have “lashed out,” to use the term of art popular for such behavior. I can justify my anger as well as anyone, and I’m already someone more comfortable with anger than the average bear (not the average human, the average bear). I have two parents who I deeply love in their 70s. I have a son who just turned 13 months old and cannot be vaccinated for a long time. I have a wife who suffers from an autoimmune disorder, and countless more friends who struggle with these and a seemingly endless list of medical conditions that have been dumped into a bucket called “comorbidities”: above-average weight, diabetes, hypertension, heart conditions. I do not join the head of the CDC in finding it “encouraging” that most of Omicron’s victims are similarly situated to so many people who I really do not want to die.

But in this post I’m going to do my level best to table my anger. To avoid my lifelong instinct to judge people. It’s not that I’m not angry and not judging them, so let’s be clear about that. I’m not trying to deceive anyone here or come across as less fully vested or less fully human than I am. But I do want to explore the disaster of the last 22 months from the perspective of compassion, empathy, and understanding. Because I think it’s instructive. And I think there’s a tragedy emerging that we are all (or almost all) having a universal (or near-universal) experience without realizing it. In fact, while believing that we are, individually, very uniquely suffering in a way that no one else could understand. And until we can get out of our own heads for a second, our own very heavy thoughts and feelings, we’re never going to realize that.

The pandemic has touched the life of literally every human being on the planet. It’s possible that there has never been a more universal phenomenon in human history, and certain that there’s never been one with this level of self-awareness: we know it to be globally universal. In that reality, it is essential to realize that, in accordance with such universal disruption, everyone has sacrificed something to this pandemic. I will not try to make the daunting and potentially absurd case that everyone has sacrificed equally: some people have lost their entire family while others have been merely inconvenienced. And indeed, the rub of that inequality has generated so much anger and misunderstanding. And thus it is fundamental to come back to the initial premise: everyone, everyone has sacrificed. They have lost connection with people. They have lost the opportunity to do the things they love. They have taken risks they don’t feel comfortable with. They have felt fear and isolation and disruption and inconvenience.

In the best of times, people are uncomfortable with change. At first, they read it as a threat and respond with resistance. So catastrophic change, a potential existential threat to the individual and even the collective society, generates massive resistance. And the most popular gut form of resistance is simple denial: this isn’t happening, or there isn’t a threat, or there isn’t anything to fear. If this sounds like a familiar reaction, be it to climate change or January 6th or 2008 or gun violence, that’s not an accident. Denial is a short-term survival mechanism. It wards off shock and the risk that we would be so paralyzed by the stakes of our actions that we would fail to act at all. Unfortunately, in the medium- to long-term, prolonged denial is deadly.

So as an individual experience, the focus of people in this pandemic has been on their own personal sacrifice. Everyone who has a friend or loved one who has died dwells on that. Everyone who has actually gotten COVID, especially with any or severe symptoms, dwells on that. Everyone who has lost a job or had it disrupted dwells on that. Everyone outside these categories dwells on the opportunities missed: the fun that was cancelled, the friends not seen, the weddings delayed or unwitnessed, the life-affirming, sustaining activities they had to suspend. I am extremely fortunate to be in this last category, for now: to date, no one I’m close to has been killed by COVID, no one in my immediate nuclear family has contracted it, and our employment has been steady and at our will throughout. I am so so grateful to be in this increasingly rare camp and I hope to stay there. But I still look at the pandemic and think of being unable to introduce my son to my parents until he was over a year old, being alone with my wife and son in a locked-down hospital at his birth, cancelling my Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim hike in June 2020, not playing a minute of basketball or doing a minute of yoga for two years, not being able to possibly move further in summer 2021, all the missed chances to see friends, and of course the seemingly endless cascade of fear, trepidation, and uncertainty.

It is this uncertainty I want to focus on next. But first take a moment and pause and place yourself in the category or categories above and contemplate everything (everything) you’ve lost or sacrificed or felt was taken away from you these last 22 months. The loss is staggering, even for those of us in the luckiest camps. That time, those years, are not coming back. And there’s not a clear road, the US capitulation be damned, to when the ship will be righted for the future. A third of Americans refuse to get vaccinated. Many immunocompromised folks and everyone under 5 can’t get vaccinated. And unacceptably high numbers of people are dying every day. Every day. A Vox article on the verge of the recent surge cribbed from one of my favorite movie lines of all-time, from Magnolia (which contributed to a category title here on this blog): “While we may be done with the pandemic, Covid-19 is clearly not done with us.”

Now if you’re really sophisticated, or have just taken the endless extra hours of fear and worry the pandemic has given you each day to consider it, you may have listed in among your own sacrifices the angst that comes with not knowing how to properly calibrate your own personal risk at any given moment of the pandemic. I’m sure there’s a German word for this. In my endless social media discussions about COVID, and even more in my perusing the posts of others, this topic has come up more than almost anything else. It’s also haunted my own discussions with my wife, in an ever-changing spiral: is this safe? Is that safe? Is it safe this week, but won’t be next week if numbers go in this direction? Most recently, it came to a head with the question of flying home to New Mexico on December 20th and, even more profoundly, flying back on January 1st. Are we going to be okay? Are we going to contribute to someone else not being okay? How would we know?

It is among the most consternating things about the pandemic that you don’t know and, in almost all cases, you can’t know. You don’t get a ping on your phone or a receipt in the mail if you contributed to someone else’s death. You can feel guilty or responsible for contracting COVID yourself, but even then you don’t know in almost any case how exactly you caught it, who from, or what exact decision led to the infection. The prolonged incubation time and, insidiously, the contagion prior to symptoms, have proven almost impossible for humans to respond to effectively. Indeed, this fact has caused so many individual Americans to tell me in the last fortnight that this is why they’re giving up trying, why they believe that quarantine and isolation could only ever slow, but not stop, the spread of Omicron. It’s just too hard and overwhelming for people to face the level of calculation of caution they’ve been left to do for themselves. So they’re no longer trying.

My argument is that the problem is not innate to the disease, nor even to the ever-changing landscape the disease’s fluctuation and variations have presented. The problem is that individuals are left to make these decisions for themselves at all.

This is an unpopular opinion, especially in contemporary hyper-capitalist not-quite-post-democratic America. We are taught that choice maximization is not only an end in itself, but the end, the ultimate good that can result from human progress. Human freedom is not measured in the ability for people to make meaningful choices about what materially impacts their lives, but in how many kinds of mustard they can select at the grocery store. Faith in the absolute decision-making power of the individual, and even more so in the appearance of same, is utterly sacrosanct. The impact of your choices on others is irrelevant, so long as you have the choice to keep choosing. If that choice is to try to collect all the money in the world, to buy 282 houses for yourself, to start a business that manipulates kids and wrecks the planet, to hoard all the patents or vaccines or masks or pills or insulin, then by God, you’d better choose it.

(Sorry, sliding into a little anger there for a second.)

The problem with a collective, nay, universal crisis like a global pandemic, is that individual choice is simply lousy at solving such problems. (If you don’t believe me, look how well individuals have solved climate change or planetary destruction through the power of maximized individual choice.) The only way to effectively respond to a global crisis is with a global solution. Short of that, nation-states as units are infinitely more effective as large collectives to cooperate in devising solutions than individuals, more isolated than in a long time, making their own flawed and imperfectly informed judgments.

The Ayn Rand and even Adam Smith crowd will maybe have to get off the train here, admittedly. The worldview stemming from the magical thought that every individual being as selfish and uncaring as possible will miraculously result in the greatest possible good is pretty incompatible with this much realism about the limits of individual choice. And if COVID-19 as a global experience hasn’t gotten you to doubt your devotion to Rand and/or Smith, I seriously doubt that my little blog post will. So, here’s your stop and hope you’ve enjoyed the ride. Everyone else can probably stay securely seated with their seatbelts fastened for the next few bumps and turns.

The evidence of the power of a government that actually wants to behave collectively and decisively to protect its citizenry is all around us. China, Taiwan, and South Korea have effectively implemented contact-tracing that has saved perhaps millions of lives (oh look, privacy is still death). New Zealand (admittedly a small island nation) and Australia, until recently (admittedly a large island nation) very effectively protected their borders and implemented strict and extensive quarantines to prevent viral spread. Denmark and Finland locked down aggressively, fully, and took care of their citizens who would otherwise suffer under such an approach, at least for the first 18 months (both now appear to be in the process of following America’s lead and giving up). And none of these countries took really drastic anti-pandemic collective actions that seem, in retrospect, imminently reasonable if you don’t start with rabid free-market assumptions: shutting down all work besides healthcare and food/essentials manufacture/distribution for a period of time, drafting citizens into manufacturing PPE or vaccines or distributing food, or even aggressive and serious vaccine, masking, and distancing mandates. I understand that all of these look authoritarian if one holds a fundamental distrust of government (it doesn’t take much suspension of disbelief – I can just try to picture my community’s reaction if Donald Trump had implemented any of these measures when the pandemic began), but proper leadership can frame these collective actions as rallying to a cause and having everyone pitch in to do their part. As a nation, we are extremely able to do this when the task at hand is killing foreigners. Why is it so seemingly impossible when the task is stepping back from our lives and priorities to save a million of our own lives? And don’t you dare say that “we were attacked” at Pearl Harbor or on 9/11 and that’s the difference. Between 2,000 and 3,000 Americans were killed in each of those events. By April 2, 2020, we had exceeded that collective toll with COVID-19. For most of January and February 2021, we were over that on a daily basis.

That was less than a year ago. And it appears we’ll be there again before the month is out.

So just as strong leadership with bold, decisive measures designed to make us feel like we’re united in common cause to defeat a shared enemy would inspire us to go above and beyond in making willing and even joyous sacrifice for collective good, the opposite of that has bred… the opposite. After some half-assed attempts to get people to largely stay home for a few weeks and a general effort to throw a bunch of money at the situation, almost entirely to corporations and mostly to those who didn’t need it, America resorted to hyper-individualism as the answer to everything. Schools and some other government-run operations faced partial closures or remote activity, but everything else was left to the private sector under the magical belief that the Invisible Hand, guided by so many billionaires and aspiring billionaires, would enable choice maximization for the good of all. “We’re not going to close down restaurants or bars or malls or movie theaters or theme parks,” American leaders told their constituents, “you have to decide the level of risk you’re comfortable with for yourself… and its impact on everyone else too, of course.” Fast-forward that approach for 60 or 90 days and the result was that there were 330 million distinct approaches and risk calculi employed in America, all of them continually changing. And everyone, no matter what strain, complexity, or self-doubt they felt internally, was ready to virulently argue that their own precise calibration was the most cautious a human could possibly reasonably employ, that they had sacrificed the most imaginable, that anyone doing less than they were to be cautious was a reckless loon, and that anyone doing more was a paranoid freak. I exaggerate slightly in degree, perhaps, but absolutely not in kind.

And thus most of the disappointment or anger that would be reasonably turned on a government for abdicating an opportunity at leadership was instead turned on each other. Instead of blaming the government for putting you in an endless series of prisoner’s dilemmas with everyone around you, you’re angry with Joe for not getting vaccinated, with Sue for wearing her mask below her nose, with Bob for not keeping his distance, and with Marie for hosting a barbeque. And look, fair enough, maybe Joe, Sue, Bob, Marie, and countless other folks should be behaving better. But they have their own Joe, Sue, Bob, and Marie in their own lives and they think they’ve calibrated more correctly. And just more importantly, we aren’t all designed, nor do we have enough information, to make decisions individually and personally that are going to keep everyone safe. That’s why we have government in the fist place! To make these kinds of decisions for us so we don’t have to.

So maybe it’s best that the government has just made it clear they’re giving up, telling people to do their own damn Googling if they want a test or a vaccine and stop crying to the US about it. In many ways, it’s what the nation has been doing since sometime in early May, just more explicitly stated.

But that feeling of exhaustion, isolation, panic, and horror that you’re facing every day? You’re not alone. It’s because the weight of an entire world’s problems, with the stakes of life and death in the balance, have been placed on your shoulder by leaders too scared to help you shoulder the burden. (Again, if this sounds familiar because of climate change…) That’s a lot to hold, probably too much. You can be forgiven for dropping it. You can be forgiven for wanting to shut down. I get it. I feel you. But I don’t think the people who put us in this mess can so easily be forgiven. And the consequences, unfortunately, are a long way from being fully realized, much less tallied.