Industries that are literally destroying the planet and human livelihood have recently found a new pitch to make themselves palatable to the average American. No one really wants to get fracked or drilled or whatever new word they’ve come up with for draining Earth of polluting resources with plenty of carcinogenic side effects for those in the region of the extraction. But even on NPR, supposed bastion of liberal bias, these lovely industries will advertise and remind us that they’re “providing jobs” for Americans. As though this mere fact alone will absolve them of any and all wrongdoing.

Never mind the quality of the job itself being done, or its carcinogenic impacts on those doing the work. Never mind the impact on quality of life for others, or even long-term potential for jobs and thriving. As long as you’re employing someone to do something, then you’d best be protected, valued, revered in our society.

I’m half expecting the Mob to come out shortly with similarly minded announcements of the great services they provide for our people. They call their work “jobs”, don’t they? “Hit-men of America, providing over five-hundred jobs a year for underemployed workers to keep our economy moving.” The drug-dealers could certainly make their case as well, though I guess Budweiser and Coors already run similar ads with more devastating effect.

Meanwhile, those who believe our planet is literally doomed if we continue to emit carbon into the atmosphere won’t even embrace the fact that total economic collapse is the only thing we can do to survive the projected catastrophe of climate change. Reports keep coming out about the improved emissions levels in the years since 2008, but everyone admits that it’s just because the economy’s down. But even the hard-core environmentalists root for jobs over planetary sustainability.

Clearly our devotion to the notion of jobs stems from the worship of The Economy (discussed here in June), but it’s hard to say why our cultural obsession with jobs is so deeply rooted. For decades (certainly my whole lifetime, and I’d imagine back to the 1950s), a job has been how a person defines their entire identity. No one can be content to be who they are, let alone a combination of pursuits and interests. People ask “What do you do?” and they aren’t interested in your creative efforts or recreational activities, unless you have somehow managed to be one of those lucky microscopic few who are permitted to live off of such endeavors. No matter how intellectually diverse or varied, you are an Administrative Assistant or In Sales or a Manager or a Doctor or a Lawyer or a Plumber. What you spend your least voluntary time doing is who you are. Full stop.

The elements of this are pervasive, not just in our daily culture, but in our very documentation. Profession is one of the only entries on a marriage license, alongside name, date of birth, and sex. Same for tax forms, a little more explicably. Profession is how we size people up, categorize them, weigh their merit relative to our own. People never ask if you enjoy the work that you do, or how you feel about that job, but merely what it is to make their own assessment of where you stack up in the human pantheon.

I would argue that it is this reality, more than any other, that has made the contemporary American evaporation of employment so challenging for the people experiencing it. Losing access to a paycheck is surely trying, though unemployment benefits do a remarkably good job of ensuring that at least those who’ve worked before can continue to eat and buy the easily breakable trinkets that connote happiness in our existence. I’ve discussed the drawbacks of failing to have a purpose and a use for one’s time, though I also believe that has enormous potential to unlock creative and higher pursuits than mere jobs can facilitate. But it is hard for those lacking an identity or a sense of self to feel inspired to create. And everything in American culture shouts that one without a job is failing in the most fundamental way a human can fail. They have not even begun to do, and thus to be.

There’s a lot of fervor in the countryside about unemployment ticking back up, to 8.3%. And there’s been a lot of fervor in the past (less so now) about the “real” unemployment number being much higher than the reported figure, for truly those who give up and don’t work as many hours as they’d like are, in some way, unemployed. And while there’s method in this approach to the unemployment number, sometimes putting the figure almost double the reported number, I’m not really comfortable saying that someone who is working part-time when they’d prefer to work full-time is “unemployed”. Indeed, the operative word here is usually “underemployed”, but someone putting in 20 hours is surely able to define themselves in terms of their work and thus ineligible for what I’m trying to discern.

Which is not to say that 8.3% is in any way a good figure. Nor is including the people who just went off unemployment because they stopped looking for work sufficient to meet the total. I think the best approach is to look at the percentage of people who are even in the labor force to begin with and see if we can discover a pocket of people we all know to be there, among the most discouraged and disheartened of them all, who don’t get to collect a check or a validly applicable self-definition to use on new acquaintances.

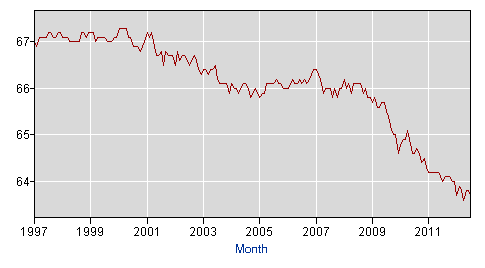

So I went to the BLS, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and came across this alarming little chart:

The x-axis, of course, are the years from 1997-2012, with data points by month. The y-axis is the percentage of the population that “counts” as being in the labor force. The labor force is simply the population of those working plus those collecting unemployment. No one else counts as part of the labor force. It’s not that 8.3% of the US isn’t working. Actually 34.6% of the US isn’t working.

Now don’t get alarmed by that figure – most of the people who aren’t counted in the labor force shouldn’t be. Tons of them are elderly, and can safely answer the inquiry of their identity with tales of past employment. Tons more are children, and can safely fantasize about what they want to do when they grow up without fear of recrimination. And a relatively good chunk are voluntary parents who devote their full-time to the rearing of the next generation of jobless fantasizing Americans.

But there’s a good healthy chunk of those people who probably should be counted as unemployed. Because this chart has a clear and distinct trajectory over the 15 years depicted. And, unsurprisingly, it’s down. Way down.

For most of the late 1990s, 67% or so of the population counted toward the labor force. It seems reasonable to draw that as a baseline for the era of rough parity/equality for women, who have recently surpassed men in terms of employability (if not, unfortunately, in terms of pay). And until 9/11 and the dot-com crash, the number is so consistent as to seem reasonable as a bellwether.

Then the number steadily declines as the economy nosedives in the wake of the events of 2001. It picks up again a bit in places, peaking at the outset of 2007 with the bubbling of the housing market, then drops precipitously in 2009 and thereafter as the impact of the 2008 crash rippled out through the economy. This is not a coincidence. These are all people who want to be working and should be under a normal economic model, but can’t. Won’t. Aren’t. They are the heart of the hidden unemployed.

The number has been below 64% for the whole of 2012. The last time it was below 64% was January 1984, when the economy was still recovering from a recession and women were less than 45% of the workforce. Today they are about 55% of the workforce. In July, the number was 63.7%, tied for the second-lowest month of the last three decades with January 2012. The lowest (63.6%) was April 2012.

So if we use 67% as our baseline and then plummet to 63.7%, that’s an extra 3.3% to tack onto unemployment, right?! Wrong. While that would put unemployment at a disheartening 11.6%, it’s actually not how math works.

You see, unemployment isn’t a percentage of the population. Unemployment’s a percentage of the labor force. Which is only fair, since you’re demonstrating the inefficiency of the labor market and it’s not reasonable to factor that as a percentage of people that include great-grandmothers and infants. So what we’re looking at is that 3.3% of the population is actually unemployed, but being excluded from the number entirely. But 3.3% of the population is equal to 5.2% of the current labor force. So the real unemployment figure should be … wait for it … 13.5%.

That’s not underemployment. That’s not working a little bit. That’s no job, no interaction with the labor force, no definition. Thirteen point five percent.

That number may not be totally perfect. Some of this may be because of the much-discussed aging population. Although, far more likely, a lot of it is about people who are young enough to keep working but too old to get jobs, so they give up. Are these people unemployed? You bet. Some of this may be because more Americans are having kids, but I really doubt that’s the case. Especially since I just looked at the original chart again and realized that this only counts people age 16 and over! So kids cannot be a factor at all. Some time when I have more time and inclination to look these up the aging issue, I’ll factor that in. But I don’t think the population got radically older during that precipitous decline of 2009, where most of the movement in this figure was found. So I’m going to stick with this calculation being a good proxy of where the real job figures stand.

What’s really damning about this figure is that the percentage of those disappearing from the labor force, if we use a constant benchmark of 67%, actually impact the real unemployment figure at a higher-than-linear rate. The way to determine the percentage’s impact on the real unemployment figure is to use a multiplier. You divide the total population by the percentage in the labor force, then multiply that by the percentage absent from the labor force. So the multiplier for 67% is 1.49, but the multiplier for our current standing of 63.7% is 1.57. That may not seem like a big difference, but it adds up.

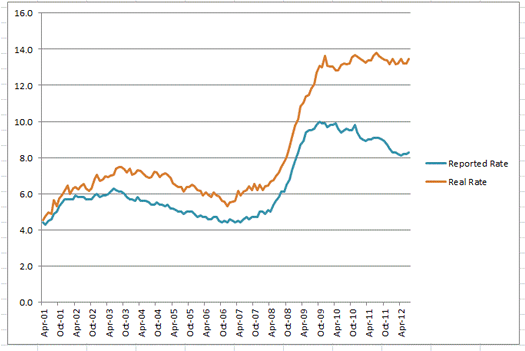

Enough abstraction and math talk. Here’s a chart I just made of the real unemployment figure by my calculation outlined above vs. the reported figure in the media. (Even though the source for my figure is also the BLS, the same source as the official media figure.) I start the chart in April 2001, both since that was on the verge of the collapse and since March 2001 was the last month the labor force exceeded 67% of the US populous.

Uh oh.

Suddenly everything makes a little more sense, doesn’t it? Suddenly it’s a little more clear why the jobs haven’t been coming back and why no one you know feels like the economy is getting better. Suddenly we have a chart that reflects how the recession has actually felt. The numbers you have been using and hearing and thinking about are as cooked as the books at Countrywide or Lehman Brothers. They’re as relevant to the 2012 economy as same.

And who are these people, this marginal 4-6% of the labor force that’s told they don’t count? They’re new graduates from high school and college who can’t get work, people told to double or triple down on debt in order to someday have a hope at that societally defined identity. They’re the older people discussed above, who’ve taken involuntary retirement at 55 and don’t know how they’re going to live to 65, let alone past it. They’re new immigrants who came for legal work through all the right channels, only to find a total lack of it available. They’re you and me and someone else you know, because it’s one out of twenty people who want work and one out of thirty adults altogether.

I may have to start reporting the real rate of unemployment every month, same day as the BLS-spun figures, just so someone is. Even cutting-edge sites like this one that report the U-6 figure for unemployment, supposedly the broadest possible measure of the unemployed that includes “marginally attached workers and those working part-time for economic reasons”, shows a disturbingly misleading downward trend-line to unemployment since a peak in late 2009. The reality is that unemployment peaked in November 2010, at 13.7%. But with current figures at 13.5%, we are functionally stalled at the peak of the employment crisis.

I cannot stress enough that these are the BLS’ own figures. They are publicly and freely available for anyone to see. You have to do two simple calculations to realize what’s really going on with American jobs.

Maybe it’s time we redefine what it means to be a person in this country?