The public debate around American society’s response to the novel coronavirus is beginning to reach an incomprehensible crescendo. As the number of cases in the US spikes to record-highs and daily deaths begin to creep back up toward levels not seen since May, the question of whether to reopen or reclose different parts of our economic and governmental operations looms large. Should we send children back to school in the fall? Should bars and restaurants be open? What about Disneyland or Disney World? Is it weird that an expectant father can’t go to his child’s ultrasound, but he could go sit unmasked at an indoor table with seventeen of his closest friends? How do we even decide how we should decide to answer these questions?

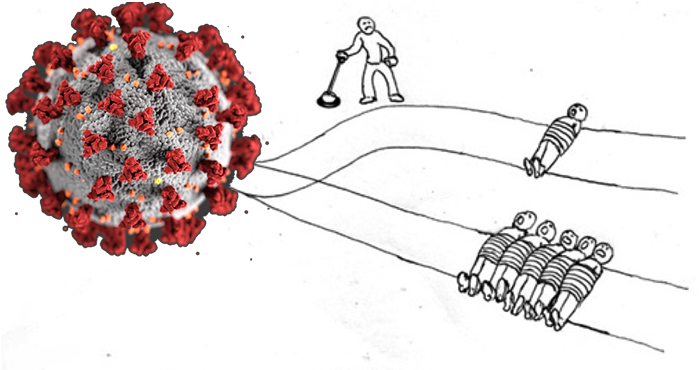

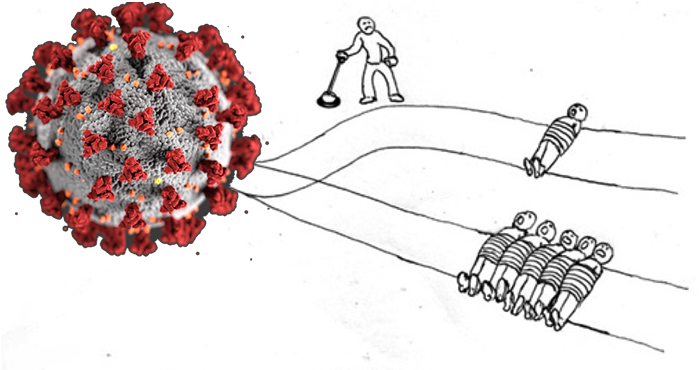

The prevailing presumed way of calculating the proper behavior for decisions in America can be broadly understood to be utilitarianism: the greatest good for the greatest number, based on the outcomes and impacts of actions. This is seen as an intuitive value structure for most contemporary students of the examined life in this society. Ask most people what they should do in the most basic incarnation of the trolley problem and they’ll throw the switch every time, killing one person to save five. (Things only tend to get complicated for most people when they have to push the one victim instead of throw a lever, or if the one victim is a friend or relation.) With the ascendance of atheism, late-stage capitalism, and science as a religion in our country, this kind of approach is taken for granted. Deontology, the main countervailing belief structure, in which everyone has innate and inviolable human dignity and the means outweigh the ends, is seen as a second-fiddle value structure. It shows up in our rhetoric occasionally, but not our actual decisions.

The big glaring weakness of utilitarianism, of course, is when outcomes are unknown. It’s all well and good to play ball with a thought experiment where the outcomes are rigidly defined: one person dies OR five people die. But we live in a temporal world in which the future is always unfixed and unknown. (Perhaps, incidentally, this is why so many neo-atheist scientists find the oddly Calvinistic belief in absolute determinism so appealing: it justifies utilitarian thought by stating that the future is utterly knowable; we just need more data to understand it.) And thus the data we rely on to calculate outcomes are probabilities rather than certainties. Unfortunately, humans are notoriously terrible at understanding probabilities, much less calculating how they impact their lives.

The trolley problem gets decidedly murkier if the runaway train has a 40% chance of killing five people and can be diverted to a 100% chance of killing one. Even though the probabilistic death toll of the unswitched trolley is 2, double the probabilistic body count of the switched trolley, there is a solid majority chance – 60% – that no one dies if the switch is left unpulled. A true utilitarian would still have to throw that switch, but good luck to them at their wrongful death (or murder!) trial when the prosecuting attorney closes on the likelihood that all six people would have emerged from the incident unscathed and the accused chose to guarantee a death.

BUT probability isn’t even what we deal with most often in trying to calculate outcomes, because having an absolute figure for probability is still a kind of certainty. As Donald Rumsfeld so unwittingly observed, most of our decisions are calculated on a kind of unknown unknown – we don’t even know the probability that our perceived probability is correct. The trolley problem quickly becomes incalculable if our reading on the outcomes carries only a 20% certainty of being accurate. After all, when was the last time you saw two groups of people tied inescapably to two separate tracks with a switch right before them? Maybe one or the other group is starting to loosen the ropes that bind them. Maybe the conductor is furiously fighting to fix the brake. Maybe the switch is faulty, or there’s a chance that pulling the switch at this speed will derail the trolley, sparing both roped captive groups but killing everyone on board. What then?

Real life is a lot more like the murkiest imaginable version of the trolley problem. And nowhere is this more apparent and obvious than when confronting the global pandemic currently sweeping the world.

If you examine all the arguments people make for closing or opening society, few of them actually hinge on a clash of values. Generally speaking, everyone is appealing to utilitarianism in one form or another, taking that structure as given. What they are debating and disagreeing on are generally questions of likely outcomes, what the impacts will be and which of those impacts will be most net harmful or net beneficial.

The initial argument for engaging in some version of quarantine/lockdown/closure was to flatten the curve of the otherwise exponentially spreading virus, enabling hospitals to keep up with the inevitable spike in cases so that fewer people would die. The cautionary tale here was Italy, whose death count surged in part because of an inability of their medical infrastructure to keep up with the number of sick. The primary argument for reopening society thereafter has been that the reduction of economic capacity is causing more pain than would the loss of life from the spread of the virus. When livelihoods depend on making money to feed ourselves (itself a dubious proposition, but that essential critique of capitalism is unfortunately tangential to my current inquiry), the job losses resultant from shutdowns do more potential harm, as manifest in starvation, suicide, despair-based abuse, and so on. Other mitigatory arguments have risen to the fore, such as the utilitarian assertion that those who are susceptible to the disease are more expendable, due to age, weakness, responsibility for their own more vulnerable state, and so on. These arguments are shocking to many who might be inclined to believe that all life is equal, or those who have loved ones or are themselves older or more vulnerable to the virus. But it’s still essentially a utilitarian argument being made: that the preservation of the most number of lives is better for the whole. And this has given rise to a new counter-counter-argument, observing how many young and healthy people have died, plus how many who haven’t died have developed seemingly lifelong conditions that will damage their future.

The biggest problem with all of this is: we just don’t know. Because the disease is new – so new that many who’ve succumbed did so because their immune system literally didn’t recognize coronavirus as a disease and thus didn’t fight it – we have no idea what even the short-term effects of contracting the virus are, let alone medium- and long-term. Yes, it’s in a family of viruses that we’ve lived with and come to understand, but it still appears to be behaving in ways that confound us. Is there asymptomatic spread? Is there airborne transmission? How often will it mutate? Will it become more benign, like the cold, as it mutates, in order to survive? Or will it become more malignant and deadly, in order to secure its place in the world? Can humanity gain herd immunity? If so, at what level of infection? And what good is herd immunity if everyone affected develops severe long-term consequences?

Utilitarianism is simply unequipped as a system of thought to engage with this level of unknowns. And unknown unknowns have a bad habit of biting us in the proverbial behind. Not just in Iraq, of course, but with asbestos or cigarettes or the burning of fossil fuels. Time and again, we make the short-sighted decision to leap into a pit that looks safe from the outside, only to discover that a hungry tiger is waiting in its shadows. Capitalism, of course (you didn’t really think I was done critiquing, did you?) accelerates the incentives of short-term thinking, especially as practiced in its current 24-hour-cycle corporatist debt-based incarnation of the early 21st century. All that matters is the immediate payoff, the instant result, damn the consequences or long-term thinking. That’s so next quarter and we’ll worry about it then. What’s the stock price today and in five minutes? We’ll base everything off of that. No wonder so many capitalists are panicking in the face of a prolonged shutdown, literally can’t imagine pausing the economy for a year to beat a virus (even if we’ve done it before). A year is a lifetime to a day trader or quarterly reporter. Better to make up data or presume we know the outcomes now rather than risk the willing suspension of operations.

But because our thinking is so presumptively tied to utilitarianism at present and utilitarianism depends on knowledge of currently incalculable facts and the incalculability of those facts leads to a wide divergence in future possibilities, it is almost impossible for anyone to agree on anything and thus we are left in a state of mass-confusion about how to proceed. Take, for example, wearing masks, which many people (including me, ultimately) think is the most obvious minimal step people can and should take to slow the spread of the virus. If it really is a fact that everyone will inevitably get (or be exposed to) coronavirus no matter what we do and that doing so will lead to a herd immunity that ultimately saves our species from the virus, then it actually is bad to wear a mask. (There’s a more subtle question about the relative efficacy of types of masks themselves – cloth vs. surgical vs. N-95 – again these depend on as yet under-tested and unknown distinctions about spread that depend on method of spread, airborne virality, and so forth.) In this instance, in fact, it would be utilitarian to hold COVID parties, to cough on everyone you know. The people who are anti-mask actually believe (or pretend to in order to justify other beliefs or priorities they have) that not wearing a mask is somehow good for our utilitarian outcome. And thus, we can’t really even have a directive from society’s authorities about what to do with masks.

And masks are by far the most minimal and clear-cut question in this whole business. Things only get more complicated when we get to something like schools and their ability to actually keep kids safe, how vulnerable kids really are to long-term impacts of virus exposure, what the costs and opportunity costs are of readying schools for pandemic operation, what the risks are to the teachers, what fair compensation is to teachers for exposing them to that risk, what value schooling can have for education in a pandemic, what the opportunity costs are for kids without school, how equitably those costs will be distributed, and on ad infinitum. At every level, there are so many variables and uncertainties that it’s impossible to have a reasonable conversation about outcomes. We are driving blindly into the night, headlights off, no moon in sight. And this is why our discussions about schooling generally devolve to a screaming match between “kids need school!” and “kids need to be healthy!” Both of these things are entirely true, and quite possibly beside the point.

At times like this, it seems clear to me (a deontologist) that we have to err on the side of utmost caution, attempting to preserve the life and safety of every individual, regardless of vulnerability or age. Americans have a habit of charging even further and faster through tangled fields of uncertainty, as though we can somehow outrun our lack of knowledge. But the reality of our circumstance is that, as a disproportionately wealthy and lucky society, we can afford to take this slow. We can afford to subsidize living and surviving through a means besides the capitalist rat-race, can afford to hit pause and wait till things are clearer to reset things. Doing so will not maximize profit for the wealthiest among us, perhaps, but it will ensure that we have more information if and when we feel we need to make a utilitarian decision in the future. This argument has often manifest as “buying time for a vaccine,” but it must be recognized (often levied as a counter-argument by the reopening crew) that this disease may not yield a vaccine in five years, or ten, or ever. What we are buying time for is more than a potential vaccine, it’s knowledge and understanding of what we are facing.

Humility is not our strong suit. Not as a species and certainly not as Americans. But the proper response to a lack of knowledge is not to fake it, to make it up as you go along, or worst to pretend that you know. Sometimes the strongest thing you can do is admit that you don’t know, acknowledge your inability to calculate how you could calculate an outcome, and stay home till you’ve thought of a different way of thinking.