“I was an alien in utero

somehow missed New Mexico

fell to Earth in Baltimore

I know”

-Counting Crows, “Dislocation”

Moments of relatability are so resonant because they are rare.

It is hard to write about alienation without feeling like you’re throwing a pity party, something people reliably recoil from, like snakes, spiders, hot lava. Ask someone if they’d rather fall asleep under the watchful eye of a giant spider or listen to someone, even someone they like, go on and on about how different and lonely they feel, and well… let’s just say they aren’t going to get a lot of sleep either way. The exception to this priority are the folks who are prone to throwing pity-parties themselves, who dwell in a state of alienation, who even question their own humanity. One imagines that Adam Duritz, for example, has disproportionate time for hearing out those who believe they might be misplaced aliens or, hypothetically, born into the wrong dimension. Of course, the mainstream critiquing population has written off everything after August and Everything After as pity-party extraordinaire. Mostly, frankly, because they are bitter that someone rich and famous has the audacity to still feel alienated. Wealth and fame are supposed to buy you out of those dread fates.

The phrase most often used with me, since pity party wasn’t quite the nomenclature, is self-indulgent. How I loathe any auditory or visual contact with this phrase even today. Writing it just made my skin crawl. For one who wrestles with self-hate on a regular basis, the notion (no, avowal!) that such struggle is all the product of some deeply selfish foisting onto others (or oneself) is crazy-making. It can be filed right next to the smug conviction of Randians (and Friends fans, no less) that all actions are selfish, that altruism is illusory, that everything one does is just about making oneself feel better or end up better off. If so, why do I feel so awful all the time? Am I just exceptionally bad at the game of life? Or, as the smuggest of them might offer, is it only the belief in altruism’s possibility that leads to such crescendic self-defeat? Just admit that everything you do is selfish and embrace it, then you’ll be happy. How convenient for those who never think about the concerns of others.

There is irony all over this, of course. After all, Counting Crows sell millions of albums each time out and pack stadiums because hundreds of thousands of us feel the same alienation as the dissociative millionaire rockstar. Or if it’s not the same, it feels the same, or close enough, and that’s pretty good for being born into large isolated flesh packets which only periodically make contact with each other. I wrote and designed a site called The Blue Pyramid, a virtual totem to feeling disconnected, and it made millions of people share my words on their own writing platforms. My silliest and most useless of words, granted, because it’s America or it’s the Internet or there were no gatekeepers or we’re all amusing ourselves to death or I’m just a hack (check as many boxes as you like). The point is that isolation, loneliness, alienation, feeling foreign: these are super-relatable. And that’s about as much irony as we can take.

It’s also hard to admit outside of songs, oblique blog posts, tortured self-indulgent soliloquies, long dark nights of the soul. It is off-putting, to say the least, to look someone full in the face, make eye contact with their bright pupils, and say “I feel like no one gets what I’m going through.” It’s a slap in that just-now-smiling-but-no-longer face. Talk about rejection. Here we are, independent flesh sacks, and I’m trying to connect with you, use my words and language and nearly four decades of socialization, by saying you don’t, nay, can’t understand. I mean, what is the point? You might as well walk around performing roundhouse kicks in every direction at random lest anyone risk getting too close.

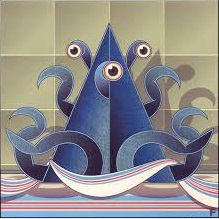

There is a lurking abyss underneath all this, laden with inhospitable sea creatures unseen in the murky waters, no seafloor in sight. It whispers to you in its rippling silence: We are all alone. We invent language and touch and society to distract ourselves from this fact. But you will never know, really, if someone else is thinking or feeling or even seeing what you do. You know the level of pressure that exists at this depth, the inability to rise from it without making yourself sick. There are lights to shine in this gloomy trench: books, music, all-night conversations of profound connection. But you can frolic on a sunny beach in July, palm trees asway, and still know, unsettlingly, that the abyss is beckoning just beyond the waves.

Every fish will flail in a new environment at first. Scoop it out of its natural habitat and dump it in another, however swiftly, and it will panic, disoriented, checking for attributes of which it had just been seamlessly unaware. Is this still salt water? Can I still see? Are there new predators? Am I in danger of being scooped again? It’s natural. The fish may not know what water is, but it can sure recognize being out of it.

And yet, there’s more than that going on. It’s not just the old standbys, the knowing rueful obsession with revision, the throat-catching near-universality of impostor syndrome, that are leaving me cold and squinting at the otherwise agreed mass. There is an increasing, creeping conviction that the lessons of life have not been good ones, that the old fears of the cost of survival are advancing like debt collectors on my cobbled existence. Life is not linear, whatever we are trained to think. This mythology is crafted by the winners, the successful, the ones who rise and keep rising, because they write the guidebooks. Just as many people have a story of where it all went wrong, cliffs and ledges, grasping for something to cling to when below was only deep, deep water.

Do you understand?