It is three-thirty in the afternoon on a Thursday, the day before the first American Parliamentary Debate Association (APDA) Championships to ever be held at Rutgers University will commence. I am in a grungy but comfortable New Brunswick apartment just over the wrong side of the proverbial tracks, a block north of the children’s hospital where I once, years earlier, spent consecutive nights keeping watch in a patient’s room with a Jonathan Franzen novel and the mantra to appreciate each minute of life in sequence as my only bulwarks against total despair. The apartment, sporting five bedrooms and two full bathrooms, is shared by five young men of various affiliation with the Rutgers University Debate Union (RUDU), the team I coached for five years, all of whom arrived at the university and the team after I left it. I have spent the week mired in a familiar combination of sleeplessness and debate geekery, punctuated by a refreshing and unsettling unfamiliarity borne of relatively new characters populating the otherwise reminiscent scene.

Suddenly, a scream emerges from the corner bedroom. Max Albert, a tousled, thinly bearded intellectual, flees. “Pasha, there’s a bug in my room! Help!”

The hailed Pasha Temkin, whose frightening thinness is augmented by a narrow chin, a penchant for wearing a long beige trenchcoat, and a floppy mop of high brown hair that a former teammate has dubbed the “white boy swoop,” responds with glee. “Let me kill it, Max! I love killing bugs.”

The two retreat into the bedroom, close the door to contain the insect, and spend the next four minutes uproariously failing to exterminate it. Whoops of laughter and little yelps of fear spill out from under the door in sequence, followed eventually by a large black fly and the two young men who, led by Pasha, chase it to the kitchen window. Eventually, they manage to shove the window open, briefly let in a second fly, and then successfully brush both away and out of the apartment. Heaving with exertion and continued laughter, the two join me in the living room and plop on the couch diagonally opposite. “I hate bugs,” Max says, smiling broadly before returning to his usual contemplative visage.

It is a rare moment of unexpected levity in a week that’s been deadly serious. Max and Pasha just finished their season as the best partnership on APDA, clinching the coveted Team of the Year (TOTY) award in dramatic fashion at the Swarthmore tournament, besting the second-place team, from my alma mater (Brandeis) in the final round and the third-place team, from perennial powerhouse Yale, in the semifinals. Not only is this the first year in two full decades that neither of the top two TOTY have hailed from the Ivy League, but it’s the highest finish for either Rutgers or Brandeis ever. More impressively, Max and Pasha are APDA sophomores, each completing just their second year of competition on the league. No sophomore/sophomore team has ever won TOTY before. Admittedly, Pasha is a Rutgers junior who “redshirted” his first year by attending few enough tournaments to not count as his novice year. But they are still the youngest team ever to take the honor, in both APDA experience and years on Earth.

Our story doesn’t begin here. Perhaps our story begins in St. Petersburg, Russia during the summer of 1995, where Pasha’s mother resides, pregnant with Pasha while I am an American exchange student spending two weeks in the recently liberated city. Did I wander past Mrs. Temkin on my way to my host family’s apartment one night, nodding briefly under the never-dark sky of a northern July? It is hard for me to imagine that moment now, internalizing that I was fifteen at the time and Pasha not yet born, hard to realize as I still feel so at home in an APDA entirely occupied by people so much younger than I am. Maybe our story begins two years earlier, when I was invited as an eighth grader by Sonia Roth to join the Lincoln-Douglass debate team she was coaching, after we shared each of our first classes at the Albuquerque Academy, third period history after the long opening assembly. Maybe it begins in 1998 at a meeting of CLEANS, the non-drinking students’ organization at Brandeis, where Adam Zirkin convinces me to come to a debate meeting despite my swearing I was done with debate heading into college. It is hard to remember my resistance to debating on APDA in 1998 when I have spent so much of the subsequent nineteen years so heavily invested in the league.

But our story, this week, really begins at James Madison University in Blacksburg, Virginia. That’s where I bid farewell to the Tulane team, to James Capuzzi and Michelle Daker, with whom I’d spent most of the last five days. It was Monday morning, April seventeenth, and Rutgers had just been announced as the seventh best team at the Madison Cup. The top six would advance to the long table finals, receive $1,000 each for their personal use and at least that much for their teams. Max had finished third the prior year, with Sean Leonard, and was counting on another top performance. Pasha banged his hand on the white-tableclothed surface before him. Michelle flashed me a look, knowing I was about to embark northward with the two of them.

“Looks like you’re going to have a real fun car ride,” she quipped.

“Yeah,” I agreed. “Seventh is probably the worst.” We went on to speculate as to whether that or eleventh was worse, noting that eleventh place is the cut-off for getting any money for one’s debate program at the Madison Cup. Max and Pasha had at least just earned $500 for RUDU, while it was still possible that James and Michelle had placed eleventh. (We later learned they didn’t.)

The Madison Cup is a tournament in its own format, slower and more rhetorical than most formats of parliamentary debate these days and unique for its six-team, twelve-debater free-for-all. Rounds take about an hour and are judged by overtly untrained “lay” judges who are supposed to evaluate who contributed the most to the round’s discussion but often defer to who sounded prettiest. Sean had twice before made finals and was supposed to return this year with Kurt Falk, but was called away to work, where he is supervised by Matt McMillan, an APDA contemporary of mine who went to Columbia and did political work in New Mexico after graduation. Kurt has been on the road with Tulane all week, flying out to see Alex and I before joining us for the sixteen-hour drive in an overstuffed van to William and Mary from New Orleans for APDA’s closing tournament of the season. At the tournament, James and Michelle hit Max and his hybrid partner from Hopkins in round one. Max won, but was chastised by the judge for being too mean. “I didn’t think he was all that,” noted Michelle after the round. “It was a regular round, but he acted like he was destroying us.”

On the other side, hours later on Monday, in the car, Max explains to me. “You know, I hit your Tulane kids first round. And the judge said there was no need to be so mean. And I didn’t even realize I was being so mean. I just have no idea in a round if I’m winning or not. So I pull out all the stops, just in case.”

I’ve seen this movie before, and I tell Max so, driving north on I-95, hours into our return from Mad Cap, two novices from the University of Pennsylvania who opened Mad Cup against Tulane in tow. “Oh,” I note. “You’re just like Rob Colonel, the Yale dino. I used to judge him all the time and tell him to ease up on people or go for bigger, more gutsy advocacies in certain rounds. And he would look me in the eye, deadly serious, and say ‘I can’t do that, Storey. If I lose, you’ll drop me.’”

Rob Colonel was also TOTY, but not till his senior year. He lost his last chance at the National Championship in semifinals in 2013, setting up this round that I chronicled at length four years ago. The next National final, of course, featured RUDU debaters Sean and Quinn Maingi on my last official weekend coaching the team before I left to move to New Orleans. I came back the next year to watch them make semifinals at Nationals. Last year was the first APDA Nationals I missed since 2009. I’ve only missed five (2004, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2016) since I first competed as a freshman in 1999.

Rutgers’ National Championship is different in a number of ways from the four in which I competed and the nine prior in which I judged. Most prominently, the league explicitly allowed the host school to seriously compete in this one. Fellow APDA historian Joel Jacobs (Wesleyan ’89), with whom I used to judge at the Stanford tournament during my years in California after APDA, informed me that Harvard won their own Nationals in 1992. I am back largely to help Rutgers try to repeat the feat.

Rutgers isn’t my home turf anymore, this weekend, now that I’m back. Or it is and it isn’t. Pasha and Max have been coached for the bulk of the year by one Shomik Ghosh, TOTY partner of a guy who infamously threw a very public tantrum at the 2014 National Championships after his team had lost to Sean and Quinn in the semifinals.^ Shomik, having never actually attended Harvard, was far less attached to the Harvard reputation’s supremacy and apparently offered to coach Pasha and Max long-distance, all the way from Michigan Law School, after he judged them at the Harvard 2016 tournament and they ultimately won, quite a coup for a school that was usually blackballed and tanked at the largest tournament of the year. Seeing the dingy and rusting John Harvard Cup in Pasha and Max’s living room when I first ascended their stairs was among the more surreal sights of the weekend, really internalizing that not only was the Rutgers-Harvard feud over, but that they had conquered said feud before Shomik offered to coach them. I think only briefly of another team that could have won that Cup from Rutgers, before the feud, Chris Bergman and Ashley Novak, who broke as the undefeated 4-seed in 2011 before I made the second worst coaching decision of my life and advised them to run a not great case to save better cases for later out-rounds. They didn’t make those later out-rounds and lost the chance to assert themselves early in the TOTY race they were intending to contend for.

Shomik is the real coach, but he’s only coaching this top team, a tradition from a lot of elite coaches to focus on just one partnership instead of the whole squad. The team as a whole is allegedly coached by the so-called “Director of Debate” at Rutgers, a gentleman hired by the School of Communication and Information after I departed who was getting a PhD but had no concept of APDA style and whose impact, generously, has been net neutral on the team. His inability to really help the APDA squad is not really his fault – the mismatch of his skills and APDA’s needs is just one of countless examples of Rutgers’ lifelong inability to avoid getting in its own way. There aren’t really PhDs who would want to professionally coach an APDA team and SC&I posted for a position that required a PhD to back the teaching load. If it weren’t him, it would have been someone else who would ostensibly run the team and meetings but be really unable to help them improve.

Shomik has certainly helped, though. He’s guided Pasha and Max into a position of focusing on social justice cases, some of Shomik’s authorship, which must have made their run to the top of the TOTY board as two white (Jewish) men more palatable to the league, I imagine. I first heard much of their casefile from Russell Potter when he came to help run the Tulane tournament in February and I was impressed. I’m excited to work with this file and this team, believing they are standing up for good ideas and important concepts that APDA has long neglected. As always, it’s important to not just win, but win the right way for the right reasons.

A couple hours after the bug, Shomik calls on speaker-phone to check-in with Pasha and Max. We’re all huddled up in the living room and he’s just gotten out of some sort of exam or class and is nearly delirious for a variety of reasons. We talk over the casefile, the deliberate choice to limit it to social justice as a subject, my contribution of an old case, run only once in history, that fits with the theme. Shomik is skeptical of the case at first, peppers it with possible opps and accusations, feeding into Max’s innate fears about the case’s possible weakness. Max goes to work on a thumbnail already dangerously close to the quick as I try to fend off the opps and for a moment it’s just Shomik and I debating for the kids, old hands sparring over the outcome of a team we’re deeply invested in. Finally, Shomik pauses to reflect, then asks one critical question about how to closeout the case in PMR, the last speech of the round. And then I answer, giving a two-minute version of the so-called collapse, answer all possible opp rebuttals in a way that turns them aside. On the other end, I can almost hear Shomik’s excitement before he expresses it, he says the word “exactly” four times in his response, exhorting Max to do exactly that if they run this case, and the four of us are all on board, all on the same page, excitedly anticipating the next day and the next and the next and when we can run this case.

Pasha and Max are a study in opposites. I realize this early in the car ride up 95, leaving the Madison Cup, though there were hints of it when I first met them both. Maybe our story begins back there, at Fordham University, the fall of 2015, when I met Max and got to know Pasha (we’d met the year before, after TCNJ Nationals 2015, at Winberrie’s in Princeton of all places, for the RUDU team dinner), when they first won a varsity outround, then another, and had their breakout performance in their first full semester of debate, making the semifinals of a 20-point tournament, what would ultimately be their second marker of a 7th TOTY performance unheard-of for novice debaters. Pasha is one of the most verbose people I’ve ever met, saying something for a person who has now spent nine years as a debate competitor and seven more as a coach, who has spent a majority of his adult life living with a debater. He processes life through speaking, often mile-a-minute, constantly verbalizing the past, present, and future in a staccato narration of what is, was, and will be. Max is nearly silent throughout, saying almost nothing as he listens to Pasha’s stream of language, weighing in often only after a heavy sigh and being pressed once or twice by Pasha. In larger groups, it is fascinating to see how this conveys vastly more weight to Max’s few words. Due to their rarity, their sparse and long-considered nature, Max’s few words come across to a group like a declaration, an edict, the utterances of Vivek Suri perhaps, or Professor Snape, or the guru on the mountaintop. By contrast, Pasha’s constant talking becomes the soundtrack, background music, and often the most important bits of it have to be repeated for their blending into the rhythm of everyday life.

It is hard not to imagine that Max has cultivated this contrast, that he enjoys his role as the thoughtful sage in the wake of Pasha’s perpetual narration. When I ask him what he hopes to achieve in life, Max describes himself as a poet. He says, understatedly, that “money is not particularly a goal” in his future. And yet this air of dreamy mystery seems wholly sincere – over the course of the week, I realize that Max lacks the fundamental confidence necessary to manifest an image of himself for the public perception. His interface with the world is the genuine product of his experiences and perspective.

No wonder, then, as Pasha says in the car, “Everyone on APDA is in love with Max, girls and guys.” He pauses. “And Max is totally uninterested.”

“I just haven’t found anyone on APDA who would garner my interest, y’know?” There is an awkward pause, perhaps as Max recalls that both my ex-wife and current fiancee were APDA debaters. “That’s just my experience.”

Their contrast and subsequent mutual admiration is what clearly works about this partnership. Pasha is forlorn and wistful when he talks about Max’s belovedness, his eloquence, his ability to command a room with a few well-timed words. At one point when describing a compliment from a mutual friend, one that sort of offends Max in the way that people who work hard are offended by their “natural talent” being complimented, Pasha blurts “Are you kidding me? I would kill to have someone say that about me!”

But it’s a two-way street. Max is clearly impressed by Pasha’s confidence, by his ability to hold forth and talk about any subject, anywhere, instantly, without carefully considering his thoughts. After all, Pasha’s fingernails are in fine shape, he approaches the world with gusto and enthusiasm, he has not once considered quitting debate. This bravado could be mistaken for a front, but it seems to truly reflect Pasha’s relative indifference to what the world thinks of him. Which contrasts highly with a discussion we have toward the end of the car ride about what Max enjoys about debate. I am essentially interviewing him after he reluctantly agrees to talk about his struggles with debate, Pasha bouncing in the front seat and trying to avoid jumping in.

“What do you enjoy about debate?”

“The validation. Winning. Being thought of as good.”

“And what do you feel most of the time you’re debating?”

“Paranoia.”

“Paranoia?”

“Fear.”

“Of what?”

“Losing.”

I have tried to convince them that earning TOTY should give them a lifetime get-out-of-jail-free card for worrying about people thinking they may not be great at debate, for worrying about losing a particular round. I have failed. But I have also neglected to tell them that once, when I was an APDA debater, I sincerely told my friend Ben Brandzel that I should be good enough to win Nationals even after a final round where the entire audience and judging panel yelled “Shut up, shut up, shut up” throughout my speech.

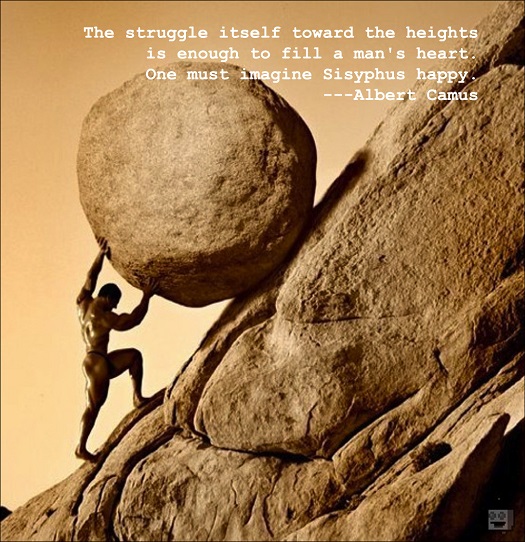

There is a very good argument to be made that the obsession some people develop with success at APDA debate is unhealthy, that it leads to mistakes later in life. The Rutgers tournament theme this year, as Pasha reminds me on the car ride, was the struggle of a debater with the concept of quitting debate and its connection to feeling suicidal. I could not possibly make this up. The tagline was “The Myth of Sisyphus” with the subhead that read:

“There is only one really serious philosophical problem, and that is quitting debate.” -Albert Camus

Select quotations from the tournament invitation for this event:

“Each weekend, we do the same thing, over and over again. Each weekend, there is but one winner, but we pretend that all have benefited. We lose our sleep, our time, our health, but convince ourselves that the next weekend, we will succeed.”

To capture the absurd, we revel in it. Victory is meaningless and arbitrary, but we celebrate it.”

“Unless you win, you lose. Even if you win, the feeling of satisfaction is momentary, illusory. Next week, there will be another tournament to win. If you don’t, you lost. You’re welcome.”

Max has said he’s functionally quitting debate after this tournament. By explanation, through a story that is later retold by several of Max’s roommates and teammates on multiple occasions, I am asked about an episode of Bojack Horseman, a show with which I am vaguely familiar for having never watched it. TOTY here is analogized to an Oscar for the character. The conclusion is that winning the award provides one good night, but the struggle begins anew the next day. I find I cannot relate. The whole point of an Oscar, or TOTY, or any other award seen as the peak of a proverbial mountaintop, is that no one can take it away. Thereafter, if anyone asks you about that thing you did (acting, debating, etc.), you have an unassailable description of reaching the top. I have spent 16 years feeling this way about winning the North American Debate Championship, even though many of my peers would not consider this the pinnacle that TOTY is.

We are at practice, Tuesday night. Max has said that he wouldn’t go to practice, but then he went. He said he wouldn’t stay, but then he stays to work on a new case while he watches a practice round. He gets so involved in the practice round that he doesn’t do much work on the case. He offers feedback to the team, Mitchell Mullen and Jeremy Kritz, the half-seed team, as they finish their debate with visiting debaters from CUNY. I first met Jeremy at Rutgers Day when he was a junior in high school and he wandered in to the RUDU room where we were holding public debates and challenging visitors to debate us. He debated Sean 1-on-1. We were all impressed and encouraged him to come to RUDU in two years. He did.

Max draws the line at RUDU Till Dawn, a new tradition started last year by the obsessive Mr. Leonard. We’d always had a Nats Boot Camp at Rutgers in the week before Nationals, famous for a lot of unconventional techniques of focus and re-adjusting thought including staring at candles, burning papers, and visiting graveyards. That, and a whole bunch of preparation. But never past one or two in the morning. Nevertheless, in the spirit of Sean, the CUNY boys, Mitchell, Pasha, and I debated till sunrise in their apartment. Max opened the door at 4:45 during our fourth consecutive round, squinted and glared at us, went to the bathroom, and returned to his room.

Boot Camp this year, aside from the Till Dawn shenanigans, has been limited by the fact that Rutgers is hosting Nationals and very little has been arranged or finalized till the last week. Indeed, when the invitation was first posted, later than normal, the Tournament Director was ominously listed as “TBD”, which I later learn is cover for the fact that Pasha is essentially TDing as well as competing, a feat never attempted. Naeem Hossein, an affable computer science guy who loves debate but lacks the time for it, is eventually named TD, but can only be there on Friday. It’s really Pasha’s show. Much of my week on the apartment couch is spent listening to Pasha call potential banquet venues in an effort to book something after the initial arrangement with Rutgers and the Heldrich fell through. Just before practice on Tuesday, Pasha, Max, and I had visited an Indian restaurant in Edison that had a cancellation of an event. They’re willing to work with the Rutgers-approved caterer that’s been booked for months. We take it. I end up paying the deposit, through Venmo after the league pays Pasha. It is nice to know that my years of fronting money for RUDU are not wholly over.

Practice on Thursday. Miriam Pierson and Will Meyer come over from Swat and Gov a case on Pasha and Max. It’s designed to play to the latter’s weaknesses so everyone gets a solid practice on what they can expect at Nationals. I’ve judged Will a lot over the years, but it’s my first time seeing Miriam. She’s impressive, giving a great MG that neutralizes most of Pasha’s LOC. Quinn has been coaching this team for two years, while traveling to an absurd quantity of tournaments to help tab. I have a moment to realize how large the footprint of Rutgers coaches is on the league now: Quinn coaching Swat, Sean coaching TCNJ, Russell coaching Princeton, and Bergman coaching Fordham. Ashley used to coach Brandeis as well, but not this year.

The next round, I judge novices Hailey Conrad and Dan Bates against the CUNY kids, who have returned after staying up till dawn two nights ago. I find them to be both great and thoroughly neglected. Hailey in particular runs an excellent case and gives a great PMR and I am surprised that I haven’t heard more about this very talented novice earlier in the year. Not for the last time that weekend, I wonder what can be done for a team that ostensibly has two coaches, but really has none for people below the top-line pair, a partnership itself comprised of sophomore debaters. I resolve to try to be more available to this team in future. If Shomik can coach from Michigan, I can certainly help out from Louisiana.

Tournament Friday. I have breakfast with Pasha, Max, David Vinarov (one of the roommates and teammates, a dedicated member of RUDU who inexplicably isn’t attending Nationals), Sean, and Geneva Kropper. David surreptitiously pays for everyone’s meal on his own birthday. The conversation is light and happy, there’s a lot of hours to go before any real competition starts. I’m excited, that tournament first-day enthusiasm starting to swell. Pasha is mostly concerned with logistics, what he might have forgotten. Max is clutching the book he’s exploring, volume one of Knausgaard’s My Struggle series, reminding me more and more of Dave Reiss by the day. I lament Dave’s absence from Rutgers’ first Nationals. He should be here.

Geneva and I return to the apartment to pick up luggage while the others scatter to do tournament tasks or, in Sean’s case, work on his day job. We discuss how poorly college prepares people for life, among other things. Then we walk to campus, past the hospital, past the Easton Avenue Apartments, where Sean used to live, and Farhan Ali before him, reminding me of late departures and the sleepy sheepish smile of one of our oldest debaters. Then down College Avenue, past the new bookstore and its RUTGERS clock, past the oldest buildings on campus, to one of the newest. Finally the enormous new Academic Building looms in front of me, a building I briefly saw on a visit over Winter Break, but have never entered. We tentatively step in to the West Wing, hoping this is correct. It is.

The building doesn’t look like Rutgers. It is gigantic and colorful and gorgeous – modern without being horrifically ugly. Big glass windows adorn the side of an enormous wide staircase, wide open spaces outside of small glassy classrooms and the giant plush lecture hall that is the object of our journey. This will be GA (general assembly) for the weekend, a red stadium-seated two-story learning palace, gleaming with the freshness of a newly built classroom and the promise of days of competition to come.

And then, we wait.

As I’ve observed in prior posts and countless dialogues with fellow debate geeks, title tournaments (Nationals and NorthAms specifically) all have the same shape. Day one, Friday, two preliminary rounds, is slow like a building thunderstorm, calm at first and full of trepidation. Then day two, Saturday, four prelims, is the longest day ever, a marathon, an endurance challenge, with eons between rounds and the feeling that wins are more dodged bullets than triumphs. Then the banquet is a sweat for all but two* teams – those who competed in the 5-0 round and know they will break whether they won or lost. The banquet announcement, preceded by interminable senior speeches, is itself a lifetime of anxiety. And then if you’re in Saturday, is a blur. The bracket resolves so quickly and careers are over and it’s just 8, 4, 2, here’s the final round, boom.

*Lately, three or even four teams have entered sixth round undefeated with slightly larger Nationals fields, so this courtesy and relief has been extended. Last year, Pasha and Max, as novices, had the good fortune to be in a 5-0 round and not have to sweat the banquet. This has come up repeatedly over the course of the week, their desire to get back to the 5-0 round. I have only debated two 5-0 rounds in my life, my junior and senior years at NorthAms. Those banquets were the best and my cortisol levels compared infinitely favorably to the same years’ Nationals banquets, where I broke from winning 4-1 rounds. For what it’s worth, I lost both 5-0 rounds at NorthAms, making all four of my title breaks on a 5-1 record. (Ben Brandzel and I were 17th at NorthAms my sophomore year – mercifully, they only broke to quarters, sparing us from being the first team out.)

Friday, true to form, is slow and uneventful. Pasha and Max Gov twice, the current favored position in the Gov/Opp dichotomy, favored over the last few years for the first time in APDA’s 37-year history. They win both rounds, but Max frets over burning early Govs and having to Opp later against better teams. I assure him that this at least gives them a marginally higher chance of getting 4 Govs over the 6 rounds. The other two Rutgers teams drop their first rounds, Hailey and Dan running the case they’d run the night before in practice and we’d beefed up, but only because the Opp team made some very clever sidesteps of their advocacy and basically conceded most of it. Both teams bounce back in round 2, though, to compile 1-1 records, along with the “Thomas Edison State University” team of Kurt and Pete Falk, making one last run at glory in their final moment of eligibility. The big eventful story that most people are telling that night is that Colonel judged Max and Pasha in round two and didn’t know they were TOTY, but hilariously said they “had potential” after discovering they were sophomores. Russell dutifully ran up to Colonel after hearing this and informed him they were TOTY, to which he immediately, in pitch-perfect deadpan replied, “I couldn’t tell.” As harsh as that sounded, we later learned he gave them a 52.5/3, so they were actually just fine.

The most eventful part of Friday for me is seeing a parade of Rutgers dinos, many of whom are here only for tonight, coming back to judge and see how far their school has come in both building heft and in hosting Nationals. Rachel Moon, Nick Hansen, Maxwell Williams, and Arbi Llaveshi check in to judge rounds and catch up and it’s great to see how many people are involved in teaching and education in some capacity. Nick tells me a wonderful story about attending some gala fundraiser for Rutgers as one of the freely invited students upon the opening of the building in which we stand and that Barchi made a joke about “Notice how it’s still just called ‘Academic Building’, hint hint.” I guess Your Name Here Building was a little too obvious, even for the pandering of Rutgers. I am taken back to the moment when I asked if we could name the Debate House (11 Bartlett Street, long since given to Dance Marathon and other frat-based organizations, despite what the RU website still says) Reager Hall, after Richard Reager, the greatest all-time coach of Rutgers debate (involved with the team from 1924-1956). I was told, in no uncertain terms, that they’d be happy to do this for a 5- or 6-figure donation to the school. It remained, officially, 11 Bartlett (Debate House or Haus, unofficially, though sometimes, very unofficially, the House of Nanners).

Friday gets out late, mostly the fault of interminable APDA Meetings, easily the least desirable and interesting part of the league, wherein debaters argue about debate rules for debate tournaments, and also when and where they should next hold these arguments. I abstractly want to go hang out with people in the hotel, but after saying I’ll stop by, I fall asleep. I blame this less on age and more on starting to get sick, as Pasha did, over the course of our week of preparation.

Saturday, though, I’m up early. I’ve talked a little about pre-debate mornings here and there and the enthusiasm they generate for me. For whatever reason, Saturday morning, usually the result of very little sleep and a too-early alarm, generate special manic energy for me as I look forward to a day of debating (or judging or coaching or just being around debate) that counteracts the minimal sleep and turns it, inexplicably, into fuel. I can only offer as evidence anyone who’s been around me consistently on debate Saturday mornings.

Before everyone assembles, before the day kicks off, I meet Myles Albert, Max’s father, the only person who ends up making me feel truly guilty that I’m not still at Rutgers (though this was not his intent). He reminds me, more than anyone else, of Wayne Zirkin, father of Adam, my junior year partner and the reason I came to APDA after all. He has the same grandiosely intellectual bearing, the same zest for communication, the same sense of being just slightly more ethereal than you in a way that makes you wonder if he is a portal more than a person. Wayne once called me out of the blue to invite me to spend the summer selling his jewelry on a cruise ship in Alaska. I was halfway through with my novel at the time, the first serious writing project I’d tried to launch, and not ready to call the whole thing off in 48 hours for an unexpected jaunt. But I appreciated the offer and acknowledged that he was on the very short list of people who try to arrange something like that on that kind of notice. I still think my parents think I should’ve gone. Max’s parents, however, like Pasha’s, who are also attending some rounds this weekend, are just learning a lesson about Rutgers that I learned hard a couple times. They don’t understand why the administration is not more overtly impressed, why Max and Pasha are not regarded with at least the recognition and esteem offered to the nearly omnidefeated football and basketball teams, the teams for whom winning one game in the year-end Big 10 Conference tournament is seen as a mammoth feat. Myles waxes grandly about scholarships and parades and even the institutional support of a coach who will go to bat for such things. I lament my absence. We used to try, I tell him, gently, but this administration, the people who oversee these clubs, will go to extraordinary lengths to waste the opportunities that debate success at Rutgers provides. In some ways, changing APDA is easier than changing Rutgers. I turn away to make sure everyone’s ready for round three.

And then the slow plod into madness. I catch up with all the old Yale dinos I used to judge who’ve returned to judge years after graduating: Colonel, Trinh, Cugini, Bakal, Li. I judge some extraordinarily close and interesting rounds, trying hard not to let my own stress about Rutgers’ performances sneak into the room while I’m adjudicating. Two Rutgers teams drop round 3, but Max and Pasha learn they’re 3-0 after an interminable period of indecision from their third round judge, who is also in tab. The other two teams are now on the brink of being out, needing to speak magnificently even to sneak in the backdoor of the break. Max and Pasha draw Opp in round 4, prep hard for the case they end up hitting about not invading Vietnam, emerge victorious with high speaks. Mitchell and Jeremy cruise to victory in their third straight Opp, squaring up at 2-2. Hailey and Dan drop, though, ending their Nationals run with two rounds to go. They resolve to have fun and learn what they can from the next two rounds and there is an almost palpable relief that the remaining rounds will be less cutthroat.

And then Brian Canares shows up to hang out, watch a round, participate in the action. Brian is among the oldest Rutgers dinos we’re actively in touch with, the Treasurer who literally made the team able to compete my first year coaching, before I was paid, before the team had any reasonable budget, when we went to each tournament begging for reg breaks and only arriving because I could donate my car to the cause. Brian squared the books and kept going to appeals meetings for more money, leveraging our fledgling success into enough cobbled money to enable us not to turn novices away from tournaments, the foundation necessary on which to grow a competitive team. It was incomparably special for me that Brian could not only make it to the tournament, but spend time catching up and then actually watch Max and Pasha debate. Doubly so for them going into that round with the their third Gov, the new case I’d given them, against a very good Yale team for the bye to the break round. Brian is one of a few seniors during my first year of coaching who I deeply wish I’d gotten to spend more years with. All have gone on to do awesome things, medical school, law school, time in Egypt, and in Brian’s case, a career in teaching, which we discussed extensively. It meant so much that he could see the journey of the team from his day to this, to TOTY and hosting Nationals in a shiny new building, that they could see the roots and origin and debate in front of someone who was there when the idea of Rutgers breaking again, much less winning a single tournament, seemed a laughable impossibility. There were few greater moments for me in that weekend.

Not only did Max and Pasha carry that round, clinching their second straight title 5-0, their second straight banquet without sweat, but Trinh talked to me about Hailey and Dan, whom he’d just judged in the pull-up round between the top 2-2 and the bottom 1-3. He talked about how awesome Hailey is, asked if she was a novice, and sheepishly admitted he’d justified for a novice for the second round this Nationals. Hailey had not only earned a 26.75 from a judge that many teams had scratched for his reputedly stingy speaks, she’d knocked out one of the pre-tournament favorites to break, 4th SOTY, from the bottom of the bracket below. I ran off to tell her and the rest of the team the good news, shortly before receiving confirmation that Max and Pasha were still undefeated. Meanwhile, Mitchell and Jeremy had won on Gov and secured a 3-2 bubble spot, depending on speaks. All was looking up as, for the first time since second round, RUDU had gone 3-0. Meanwhile, unfortunately, the Falks had been knocked out, still smarting over a fourth round decision they disagreed with, and dropping fifth round to go to 2-3.

And then, the bubble. It wasn’t actually a bubble for Max and Pasha, of course, but it was a bubble for an inordinate number of teams. The second TOTY team from Brandeis, who were pulled up to hit a 5-0 team from Princeton. Mitchell and Jeremy, we hoped. Thirteen teams who were 4-1, knowing they were a win away from clinching a spot in the coveted octofinals. And twenty-five more who were 3-2, needing both a win and good speaks and sufficiently good previous speaks to secure their spot. Two of whom I was judging, Harvard CH and Fordham A.

My round was fascinating, a narrow case offered by Harvard, well Opped by LOC and resoundingly defended by what seemed like a very good MG. But then atop the MO speech, Fordham showed me that all of the Gov assumptions rested on a defense of the status quo, that this was actually Opp’s ground, and that the incentives would be different than status quo incentives in the Gov world. It instantly turned what had seemed a ferocious, possibly round-winning MG speech into a paper tiger, and did so with something I’d seen very little of all weekend amongst the stressful razor-thin rounds of Nationals: humor. The Opp block was easily the most entertaining and effective of my weekend and the PMR’s only attempt at mitigation was rightfully called new by the Opp team. I allocated a 53/3 to Fordham and vaguely wondered whether they would be the annual free seed to make the break. Moreover, I relished knowing their fate when I would have the opportunity to withhold same information from Bergman all night, instructed as per Nationals tradition to disclose nothing of the results of round 6, maximizing suspense for the 38 teams on some form of the bubble.

It did not take long for me to be confronted by Bergman. He was standing with his team, Ellen Hinkley and Marcelle Meyer, both of whom were pointedly not asking me about the decision, as I returned to GA after handing in the ballot. He tried to be vaguely coy in the way he was asking me, but I got very near his face and smiled broadly. “You know, Bergman, I was elated to see that I was judging Fordham in the bubble. Because I knew it would mean I knew something you wanted to know all night and there would be nothing you could do about it. It’s like double Christmas!”

Much of the rest of the evening was spent with him trying to work out what that meant, Princess Bride-style, for his team’s chances.

The banquet venue turned out all right. The big change from normal Nationals, besides actually having enough seats for everyone, was the lack of alcohol. And while some of the dinos and other folks whinged about this at first, it made for the most respectful round of senior speeches I’ve possibly ever seen. Senior speeches, one of my favorite traditions of Nationals, indeed of all of APDA, are the farewell monologues from graduating seniors where they are given a free mic to discuss whatever they want, good or bad, to offer thank-yous, call-outs, shout-outs, condemnations, or observations. They are often talked over by drunkards in the back, usually themselves long since graduated dinos who are among the oldest in the room in age only. This year, however, people listened. And it was an important year to listen.

Mars He, APDA’s President-elect, a decidedly affable Harvard debater in the tradition of Allen Ewalt (indeed, the entire Harvard team has seemingly switched over to a large squad teeming with a multicultural, gender-balanced group of very friendly debaters^) MC’ed the speeches. And after a frantic search from the intended opener, Nathan Raab, the opener was instead Megan Wilson from Yale.

Her speech was somber, measured, and excoriating as she described the uphill battle she faced and her long-time debate partner faced as highly successful women on the league, much of the setbacks coming from initiatives and groups that were designed to help women and people of color succeed on APDA. She was specific in calling out the caution and gendered language used to attempt to limit her success or make it fit patterns expected to be more palatable for the still too sexist league. Megan going first set the perfect tone for the night – it enabled many people on the fence between a few thank-yous and a genuinely necessary call-out to tip the scales and go for the call-out, the message APDA needed to hear. APDA spends a tremendous amount of its time being self-laudatory for an event that, while decidedly intellectual, can often live on the border of sophistry and grand-standing. Senior speeches are one of our built-in counterweights, where we have to listen to the voices we’ve excluded or minimized and, hopefully, resolve to do better.

As the speeches went on, the contrast between those by white men, usually a bevy of calm thank-yous and plaudits for friends, and those by everyone else, punctuated by hardship and unfairness, could not be missed. Among these latter were both speeches by the members of Fordham A, Ellen and Marcelle each taking time to criticize APDA’s seemingly innate sexism but also observe how easy it had been to build a gender-balanced (or, indeed, “matriarchal”) team at Fordham by simply creating a culture of talking to everyone, regardless of their background or perceived skill at debate. There was a call-out about a team showing up with tons of novices, only two of them female, and then ignoring both female novices while they got left behind in housing. It was certainly depressing to see that APDA still struggles with these issues, even in an era where the APDA President (outgoing) is a Black woman, Jerusalem Demsas. That said, she’s only the second woman to be President of APDA in its 37-year history; the first was Ashley Woods in 2011-2012. Yeah, if you’re scoring at home, that’s 30 straight years of only male Presidents. Though, hey, still better than the US as a whole.

But it was also heartening to see that so many people made this issue a centerpiece of their speeches, felt compelled to share their experiences, felt that tonight, the most important of all nights on APDA, they would be heard. I was sitting with Alex Jubb and Deepta Janardhan and talked with them after the night about whether this trend reflected a worse overall culture than their time or my time or just meant that the culture was thawing enough so that people felt they could talk about it and push things to improve. The consensus seemed to be the latter. It’s one of those weird evolutionary quirks of APDA that things have not been linear in gender and racial balance. For example, three of the four National Championship teams in my era included a Black man. And one included a woman, who, going into this year, was the last woman to win APDA’s Championship, in 1999. And of course, in 2001-2002, we had the first female SOTY (Speaker of the Year, the top individual honor for the season), capping a top ten SOTY that had exact gender parity (5 women, 5 men) for the first and only time in APDA history. Just six years later, in 2007-2008, the top woman in SOTY finished the year ranked 19th. How did this happen?

And this is not to say, as Kate Myers pointedly reminded me later, that our era was a bed of roses or treated women well. But the results certainly speak to a gulf in opportunity to succeed and how debaters are perceived that cannot be ignored. Gender parity or a female national champion are not proof that everything is solved, but an 18-year drought in the National Championship is more than sufficient proof that there are really significant problems.

The senior speech that stole the show was from Jemie Fofanah of Temple University, a woman I remember judging at TCNJ Nationals two years ago, who I had been quite impressed by. She delivered a slam poem calling out APDA’s sexism and especially racism, observing how many people will run cases about people from her background but refuse to acknowledge her as a person, refuse to live their life in a way that accords with how they talk about her people. And worse, they are basically exploiting black and brown bodies to win a round while never really considering how patronizing they sound or how inconsistently they apply these values. It was a thunderous condemnation, punctuated by pointed requests for Mars not to cut her off (the early senior speeches had not been time-limited, but the banquet hall owners were getting restless late in the night and they’d tried to implement a 3-minute limit to that later speeches, which fortunately was basically not enforced). It was the only speech to receive a standing ovation from more than just the speaker’s team and close friends.

It is worth noting, here, that the last two senior speeches of the night, delivered by the ranking seniors on the outgoing APDA Board, the six-person elected panel of students that governs the league, were given by women of color. Yidi Wu, the outgoing VP of Finance and Jerusalem, the outgoing President, struck a more hopeful, mixed tone than many of their prior speakers. They acknowledged the league’s failings, but also its progress, saying emphatically that they didn’t want novice women to be sitting at this banquet and get the impression that they should quit, that they would graduate in three years embittered, that they couldn’t contribute to even more progress in that tenure. And while such exhortations often ring hollow, they ring truer from this testimony than they might from other sources. And in the context of APDA’s cultural shifts from ten years ago, they ring possible. This is not the corporate world telling ambitious young women there may be exactly one more slot open for them at the top by the time they get close. It is not, of course, better than it should be, and that is unfortunate. And now, it is time for the break, almost suddenly in light of the surprising brevity of these last two speakers.

Mars wraps up and the very tired tab staff, Diana, Quinn, Adele Zhang, Anirudh Dasarathy, and Dan Takash, assemble on the stage. They have been here for over an hour with the break ready, the list divided up into teams closest to them to announce. Unlike in past years, even the Nationals break seems subject to a one-clap advisory, something I find jarring and out of place in the midst of the most important and difficult break announcement of the year. Of course some teams still whoop and cheer for their own, none louder than Fordham upon announcement that they are indeed a free seed in this year’s break, that their sixth round performance was enough for them to make the elite cadre of 4-2’s in the octofinals. Rutgers (Max and Pasha) are in, but we knew that, as the sixteenth team is announced, they are the only Rutgers team to make it. We still don’t know the outcome of their sixth round, nor will we till the following morning. As the dust settles on the list in my hand of breaking teams just announced, I realize two more things of signficance:

(1) That’s still a lot of Yale (5 of 16 teams).

(2) Quinn didn’t announce his own team!

Quinn did announce Rutgers, yes, from where he graduated in 2015. But he didn’t announce Swat MP, the team he coaches, making their first Nationals break during his two years of coaching there. I certainly enjoyed a good fake-out in my days of tabbing and announcing breaks, and would in fact routinely push the most surprising Rutgers team into the last break announcement slot of the “no particular order” to maximize their suspense. But it’s another step entirely to watch your coach announce his alma mater and then stand back without announcing you when you’re on the bubble! But they are in and jubilant and only a touch mad at Quinn.

And Fordham, indeed, is only a touch mad at me. After fist-bumping Max and Pasha, I head over to tell Fordham about sixth round (they know, of course, but a little bit more) and I see a cavalcade of tears and hugging and a too-smiley attempt at a glare from Bergman as he gets swept into the maelstrom. One of the debaters tells me that she was pretty sure they’d won sixth round, but kept having doubts, but still thought they were speaking too low to make the break. “Isn’t this better?” I ask rhetorically. “Isn’t this better than just knowing the whole time?”

Laughing through weeping is my only real reply, along with a half-hearted tongue-in-cheek condemnation from Bergman.

As the crowd thins down and people pile into Ubers, rental cars, and school vans, I confirm with Max and Pasha that they don’t want to work tonight. Max expresses a brief concern with the casefile in light of Jemie’s moving speech, but Pasha brushes this away. Pasha is now deeply sick – he is about two days ahead of me on a cold and our rhythm of nightly tea has not been enough to stave off the worst of it for a man running both a National tournament and debating to the top of said tournament on a weekend where New Brunswick was hit with a surprising cold snap after near-summer weather. They both need rest and I am starting to feel my own illness and like I’m not of much use. So much of Nationals is usually about preparing cases for Gov, but the current perception of Gov’s superiority means that prep seems limited overall. Cases are all likely to win, the idea goes, and opping is a crapshoot, so you just wait nervously and hope for the best. Until tomorrow, then.

Tomorrow comes, early, but there is a significant delay from tab in assembling panels to adjudicate and we end up waiting over an hour in a tense anticipation. I have told both Fordham and Rutgers folks that I have a premonition they will hit in the octofinal round. This sense mostly comes from poetry and the idea of vaguely where each team is likely to be in the bracket, but this also counts on the notion that Rutgers might have beaten Princeton in round six. When pairings go up, we learn that they did not, that Rutgers has fallen all the way to the seventh seed, for a date with ten-seed Brown, Yidi and Caleb Foote. This pairing is complicated by the fact that Pasha debated with Caleb last weekend in a “hybrid,” winning the final regular season tournament of the year, but also exposing a lot of potential cases to this team. Max, nervous, not expecting such a strong team, suggests a case I haven’t even heard about, but it’s never lost and he jokes that “there’s like one opp”. Both Pasha and I are concerned enough about his concern that we fall in line with the case choice pretty quickly, I make a cursory review of the points and confirm that they both feel good about it. We tell Brown we’re Goving, I tell Max to breathe, we disperse to our rounds. I am judging, on a panel with Colonel for perhaps the first time in our lives, between the 8 and the 9 seed, this year the bottom two 5-1 teams. I head off to my round.

Judging Nationals out-rounds when one has a vested interest in other rounds is a unique perspective. I talked with Vivek extensively about this once, how the feeling of lack of control in coaching is greatly exaggerated because one can’t even watch, can’t be in the room, and the demands of judging (no less such important rounds) takes all of one’s energy and focus to get right. This was especially true in this round, what proved to take the longest to adjudicate, a narrow 2-1 win for William & Mary (Jerusalem and Jessica Berry, a novice) over one of George Washington’s two break teams. The round was fast, messy, and unclear, leading to a tortuous adjudication process in the new world of consensus panels, which I feel are the worst part of British Parliamentary debate now imported into APDA. Traditionally, out-rounds involve a straight and independent vote of the odd number of judges assigned to an elimination round. Each person decides their ballot as though they were the only judge in the room, writes Gov or Opp on a little scrap of paper, and then hands it to the chair, who tells everyone the winner and their margin. Then the judges discuss the round with each other for fun as they head back to tab to report the decision.

With consensus panels, on the other hand, debaters are charged with not only winning the round in which they debated, but also winning a second round in which they cannot participate, that between the judges. While consensus panels are sometimes handled reasonably and fairly, questions of the relative reputation and ability to debate about the round between judges often sneak into these “consensus-building” sessions and certainty about the round from some judges can be mistaken for a conviction that should sway a whole panel of uncertain judges on the other side. Even in the best case scenario, when a straw poll comes back unanimous, it often takes ages for a consensus panel to agree to finally call it a consensus (this would happen in the semifinal round I would judge later in the day).

Colonel, Lauren Blonde, and I had a fun, lengthy, and agonizing discussion, feeling really guilty for holding up the tournament and making everyone wait. But ultimately we voted 2-1 for William & Mary, on the same lines of our initial straw poll, making the only difference from regular voting the extra 45 minutes it took. Hilariously, the round was so close that our reporting of the outcome was contradictory and almost led to a colossal error in the announcement that would have created a lot of headaches and heartaches for tab and teams, respectively. In the end, everything was restored to equilibrium before such damage was done.

But not for Rutgers. Their tournament was over, they were out to Brown on consensus, the first loss for that case. It had gotten too wrapped up in the con law aspects and Brown had done just enough. Cugini, on the panel, told me it had been really close for all three judges, but they all saw it the same way. Pasha was devastated. Max was gone. I was bereft, but it’s National Sunday and there was only so much time we had till it was time to go judge again. This time, it was the same William & Mary team against another GW, consisting of Andrew Bowles and Nate Sumimoto, a match-up of the top two SOTY speakers (separated by a 99-98 margin at year’s end), both paired in “pro-am” partnerships with novices.

The round was a showcase, a fantastic display of rhetoric, but ultimately an incredible strategic play by W&M in Gov. The case was built as a series of red herrings with the third point as an “even if” backup to stand and win even if all the herrings had been caught and skewered. Opp spent their entire time on the herrings, dropped the key point in LOC, MG failed to call much attention to it, and PMR kicked the door down on a round that Opp had seemed to be crushing since four minutes into the Opposition’s opening. It was a masterpiece of strategic debating in a National Quarterfinal, all the more breathtaking for the fact that I’d literally believed Gov would be incapable of winning at the outset of PMR.

Semifinals lacked the same rhetorical verve, featuring a dull and thick case intended to slog the Opp (W&M yet again) out of the round, which it did successfully, arguing, of all things, that pork barrel spending should return to Congress. I was uncompelled by the notion that the relative death of pork barreling has accelerated the era of gridlocked mutual hate in American representative government, but Gov did more than enough to prove it for the purposes of the round, against little resistance from a team that had undertaken an impressive run but come up just shy of the final. And then we were there, the final round of the National Championship, just like that.

I was off the judging panel, apparently the result of a scratch from a Yale team that had been running deeply interesting and philosophical cases all weekend but apparently feared my judging because I share the “old dino” reputation of being “low speaks” (I gave five 26.5’s this weekend). This Yale partnership, Miles Saffran and Jim Huang, had been in the position I’d said all tournament was the catbird seat, the top-speaking 5-1, in this instance, the three-seed. This team, whoever they are, usually loses a middle round in a close but high-speaking position, then goes on to cruise through rounds five and six by wide margins. The team has a structural advantage by being loose, a key component of success at a title tournament. Max and Pasha were many things this weekend, most of them great, but they were never loose. Max, who has returned to the tournament, seeming relatively okay with everything, may not have a loose bone in his body. Pasha seems capable of being loose, sometimes, but not when he’s running a tournament. And maybe not when there’s talking involved – his intensity may be too much. Miles and Jim, meanwhile, as they finally return to the beautiful GA, now adorned with glittery trophies for the season and the tournament, seem to embody that loose feel native to 2- and 3-seeds, to the top 5-1. Their opponents, hailing from the other semifinal, are Swarthmore MP, Miriam and Will, who’ve made it out of the 12-seed like any good NCAA upset squad. Adele asks me to time and I settle in to watch the fireworks.

The round proves to be excellent, ticking most of the boxes of what a final round should be, though periodically there are moments from Gov reminiscent of the 2010 final from Harvard, Cormac Early and the late Kyle Bean running “magic empathy”. Gov’s case, ostensibly, is that empiricism is irrational. As they run the case and flesh out the points, however, their stance starts to appear something more like “empiricism alone without help is insufficient,” which is somewhere between a slippery advocacy and a collapsing tautology. Miriam, however, in LO, is more than up to the challenge of both making the necessary observations to ward off any possible collapse and continually returning to humor about empiricism as its own proof. The round, ultimately, is extremely well engaged from all four speakers, exploring the nature of reality, knowledge, and epistemology from an entertaining and accessible vantage. But after rebuttals, it’s pretty clear that one side has convincingly carried the day.

Right before floor speeches, now delivered after the round and away from the panel to prevent them from swaying the outcome of the all-important round, I head over to Quinn and Deepta, grabbing for Quinn’s surprised hand. “Congratulations on coaching a National Champion,” I say.

They spend the next forty minutes asking me if I’m that sure Swat won and will prevail. I say I would have to be pretty confident to come over and congratulate him, but at the same time, I think it should be that clear. Obviously, with consensus panels, anything can happen, and one obstinate judge could sway the whole group, especially if they claim philosophical authority on such a high-minded round. But I’m confident and say he should be too.

Adjudication takes more than an hour.

But there’s plenty to do in that hour, the cascade of season-long awards, the eventual National awards from this tournament, with the final round reserved for the very last. Among these is Quinn winning the Distinguished Service Award (DSA), thanking him for a year of running countless tournaments in the south while always offering assistance to everyone. He is surprised, or seems it, but Deepta and I both knew it was coming. He gets back to his seat and says “that’s nice, but it’s not what I care about,” referencing the looming unannounced final round. It occurs to me that if Swarthmore wins, Miriam will have broken the 18-year streak of all-male National Championship teams, dating back to my freshman year, comprising just shy of half the time the league has been in existence. Women won in 1997, 1996, and 1985, but never from 2000-2016.

As I remark to Deepta, considering this, “if it can’t be our boys, I hope it’s no one’s boys.”

And then, finally, at long last, the announcement. Swat on consensus. They are National Champions. Finally, a woman holds the title again. And a guy I coached to National Finals has coached a team to the National Championship. My coach, Greg Wilson, who debated for UConn, never made the out-rounds at Nationals, losing a bubble round in his last opportunity. But he coached me to National Semifinals, along with another team (Zirkin and Jordan Factor) to National Finals. Then I made Semifinals and coached Quinn (and Sean) to Finals. And then Quinn made Finals and coaches Swat to the title. All one can ask for is for the accomplishments of those who come after us to exceed our own. For this to be achieved in both debating and coaching was a satisfying solace to Rutgers not winning their first National title. For Swarthmore, it was their fourth, putting them actually pretty high on the all-time list (only Harvard [10], Princeton [6], and Yale [5] have more). The Naval Academy (1983) remains the only public school ever to win. The Ivy League has won 26 of the 37 titles.

People thin out, hugs and goodbyes and celebratory photos are taken, people thin out further. It is, eventually, Pasha, Max, Deepta, Russell, Mitchell, Shanti Hossain (Pasha’s girlfriend, the official tournament photographer, to whom I am indebted for the lovely photos in this post), and me. And a very unclean GA. And the breakfast display still outside Scott Hall, where GA was going to be, then wasn’t, this morning.

We clean. We pick up items, we mine behind chairs and under desks, we clean from spills of illicit food and beverages and pick up keys and pens and IDs left by people long before the tournament. We scour this beautiful room that didn’t exist on the campus a year prior, the heads of the team, the dinos, and a generous person who has given a lot to the tournament. And there’s something about this time, this bagging up trash outside GA and then heading to Scott Hall to move tables and do it again, that feels like the seminal moment to me. Behind Scott Hall, which hosted our team meetings in 2010-2011, the breakout year, the first time RUDU was in the top ten of anything, in front of Murray Hall, the host for the next three years, the glorious runs in COTY and Nationals and all that was witnessed. Bagging curdled milk and stale coffee and the rock-hard remains of a bagel under the cover of night, just beyond the watchful gaze of William the Silent, down Voorhees Mall.

This is water. This is water. Under the bridge, past the banks of the old Raritan, and into the ground, to be dredged and drunk in future years by those yet unborn who will debate ideas we have yet to imagine.

I fling the last black plastic bag, lopsided and slightly overfull, up over my head, into the dumpster, and hear it land with a satisfying thunk against its neighbors. Smacking my hands against each other in an exaggerated tone of “mischief managed,” I notice that just a little creek of whitish coffee has landed on my sleeve, a rivulet running down the Rutgers Student Life sweater I’ve been wearing for three days straight.

^A couple of small references, including a name, have been removed from this piece at the request of an individual referenced.