During the Iraq War, I made an effort not to stand for the United States’ national anthem while it played. The context for this was almost always sports games, because even though ESPN Radio (which I listen to a lot between Uber drives these days, while the NPR station is playing jazz and I’m waiting for the BBC World Service to come on) insisted (before this past week) on shouting down any caller who brought up politics, sports have been insidiously intertwined with politics for decades in this country. We have military nights, we have anthems before everything, we have the ongoing extra displays of patriotism since 9/11. Like so many elements of our society, we are made to forget that the default setting of what we perceive as normal is, itself, a political statement. We live in a deeply politicized reality, one where every student is made to swear unwavering loyalty to a piece of cloth every morning in a ritual that, were it discovered in North Korea, we would lampoon as the result of creepy brainwashing.

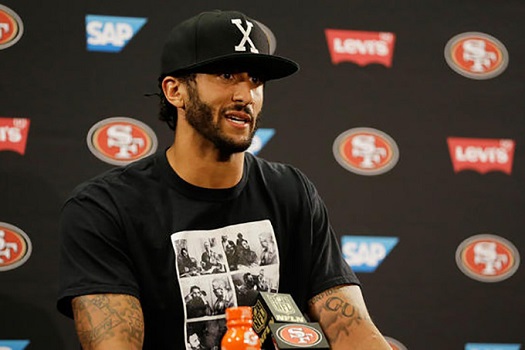

I say “made an effort not to stand” because there were a couple of times during that war that I can recall reluctantly and awkwardly standing, because I didn’t want to make the person I was attending the game with uncomfortable. In light of Colin Kaepernick’s brave public protest (ironically being called a “stand” in many quarters, which I can’t reconcile enough to invoke), I feel even more ashamed than I did at the time about these compromises. I at least a couple times went to the bathroom during the anthem at these times rather than do my customary sit, often when attending the game with just one friend, often someone more conservative, and I just didn’t want to get into the difficult debate in that moment. And, frankly, it’s not just this piece of cowardice that demonstrates to me the difficulty of Kapernick’s incredible protest. It’s the fact that during most of my Iraq War seatings, I was accompanied by others who joined me in the protest. My wife at the time, and two of our very good friends. I’m not even sure we even talked about it specifically or that thoroughly. I’m sure I discussed it with my wife at some point, but it felt like an organic thing. But it’s way easier to sit as a group of four than solo. Admittedly, I also did this when I attended baseball games by myself.

I’ve always been uncomfortable with the anthem and the adoration of the flag, turning my back on the ceremony at times during high school and rolling my eyes and sighing awkwardly, hands buried in pockets, during sports game ceremonies both before and since Iraq. Kaepernick has reminded me that the Iraq War, while poignantly awful in American history, was by no means the only thing warranting this small silent signal of resistance. And deep down, I knew that. I just got tired of the angsty separation from the rest of the crowd, the terse comments from a handful of people, the (at least twice) slaps from older gentlemen accompanied by “get up!” (this only happened when I was alone). No one ever tried to engage me in why I was doing what I was doing. And only once did I see someone else in a ballpark joining me in the (lack of) move, though admittedly sitting while everyone else is standing can make it hard to see (except at Oakland baseball games, where attendees are few and far between).

The anthem stands for might-makes-right, it stands for the notion that a piece of cloth is more important than human life, it stands for the idea that all manner of human violence is worth it if our empire prospers. It is, even before people started talking this week about the grotesque verse taking joy in the death of freed slaves, the embodiment of what I object to about the American Empire. Glorying in war, the utilization of war as a means for our own advancement, the prioritization of cloth over life. And its universal proliferation before sporting events, before gatherings and conventions and convocations is, like the pledge, a little piece of ongoing indoctrination into this militaristic value set before every little ceremony. Kill for your flag. This is what’s important.

During the Iraq protest, I had dreams of starting a campaign that I would call Don’t Stand for It. Mostly, I was lonely and wanted more people to sit with me, because it felt like the right kind of protest that was small but powerful and well matched with what was being protested. It’s an anthem of war, so let’s not honor that during one of our many aggressive, ongoing, deeply unjust wars of imperialism. My follow-through on these kinds of campaigns is notoriously bad, so I can’t really lament not registering that website or starting that campaign – it wouldn’t have gotten more than a handful of supporters anyway.

This is what makes Kaepernick’s protest so inspiring and exciting. He has the platform to broadcast his message, the power to get people to join with him. He has reminded me that I was just copping out during all those Pelicans games, that the arc of American injustice is long and bends towards the flag. It took momentous bravery for him to make this statement, in a year when he wasn’t even assured a starting position on his own team, at a time in our media culture when he knew he was deliberately putting himself in the crosshairs of every zealous racist, warmonger, so-called patriot, and conservative in the nation. He knew exactly what kind of firestorm of criticism and anger would beset him and he sat, alone, regardless. This is what heroism looks like.

As has been well documented in the American media, much of the predictable backlash to Kaepernick’s sitting has been unadulterated racism, newly distilled in the resurgently open bigotry that accompanies many factions of Trump supporters and the opponents of Black Lives Matter. But the mainstream backlash is more insidious – the commentators on ESPN alleging irony that Kaepernick is “protesting a symbol of his right to protest” and saying that he is “disrespecting veterans who are fighting for his right to protest like this”. It’s one of the most knee-jerk, rote, and incorrect assumptions about our flag, anthem, and military: that they have something to do with our freedom. If you can even get past the initial issue that tools of mass-coercion and imperialism can ever be about freedom, even if that “freedom” is coming on the back of oppression of those both outside this country and locked up in this one.

America has faced nothing remotely like an existential threat since World War II. Arguably that war and the Civil War were vaguely existential threats – I could make a pretty good case that neither of them were, but I don’t want to get into that right now, since it’s irrelevant to my main point and my thoughts on WWII are already pretty polarizing. Yes, there are a few WWII veterans still around. But setting those folks aside for the moment, the veterans being most virulently defended in the media against protests like Kaepernick’s fought in wars that were unadulterated, naked imperialism that had nothing to do with defending American freedom. In Korea and Vietnam, the fight against popular communist leaders was packaged as pro-freedom, even though said leaders would have won national democratic elections in their respective countries. Ditto countless covert military operations in Cambodia and half of Latin America. Then we have Iraq, Afghanistan, Iraq again, Libya, the unending war to kill everyone in every country who disagrees with US foreign policy. These are not responses to existential threats or really threats at all – they are self-justifying pursuits of oil, business interests, and the notion that American hegemony is the natural order of the planet. You can think it’s noble if you want that people voluntarily sacrifice their time, energy, and livelihood to sign up to kill for their country (I don’t). But it’s just incorrect to say that they do so to “defend our freedom”. Had we fought zero wars since WWII, we would have exactly the same freedom we do now. In fact, I would argue, much more freedom, because there would not be people in the rest of the world who want to exact revenge on America and its people for the violence it enacted on them, their family, and their country.

Of course, most of those folks in the military didn’t feel like it was much of a voluntary choice. Our military is comprised of disproportionately poor individuals, disproportionately minority individuals, those deprived of opportunity at every turn who were both indoctrinated to believe that killing for your flag is noble and often misled into thinking they’d be safer and better compensated for their sacrifice. No wonder, then, that #VeteransforKaepernick has caught fire on the Internet, that (as in every era) it is veterans of these awful wars who are often the first to rally behind those against the next war. American soldiers return to the nation shattered, traumatized, and suicidal. And most of them seem to understand that Kaepernick’s protest helps honor their loss by trying to prevent the next generation from having to endure it.

Of course, Kaepernick’s protest is not primarily about war, though these realities are a fitting response to the obnoxious mainstream argument saying that his protest is well-intentioned, but he picked the wrong means (I have yet to hear one suggested alternative means, needless to say). It’s about Black Lives Matter, increasingly becoming the most important movement of our generation in America. A movement that has renewed a national conversation about our nation’s historical and ongoing oppression of a race that has endured slavery, slaughter, mass-incarceration, and minimization every day of America’s history. His protest is helping pivot the movement to the spotlight in a moment that is not just the week after another horrific police execution of an innocent Black citizen. He is helping to raise the issue with every week of the nation’s most popular sport, reminding the national audience that the Black players they revere each Sunday are of the same race as those they (at least de facto) support incarcerating and gunning down seven days a week.

Colin Kaepernick’s protest is everything a protest should be. It’s risky and brave, it’s targeted and precise, it’s powerful and profound. Every day, more people are sitting with him, agreeing that Black Lives Matter and that our anthem and flag are not more important than oppressed human lives. Next time the anthem plays, don’t stand for it. Thank you, Colin, for reminding me, for reminding all of us, what truly matters.