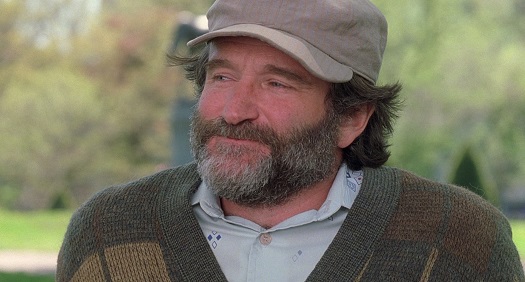

“And when the guy said, ‘Well, do you ever get depressed?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sometimes I get sad.’ I mean, you can’t watch news for more than three seconds and go, ‘Oh, this is depressing.’ And then immediately, all of a sudden, they branded me manic-depressive. I was like, ‘Um, that’s clinical? I’m not that.’ Do I perform sometimes in a manic style? Yes. Am I manic all the time? No. Do I get sad? Oh, yeah. Does it hit me hard? Oh, yeah.”

-Robin Williams, Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross, 2006

The way people talk about suicide in this country infuriates me. Because most of it is very much a way of not talking about it. People treat suicide like it’s ultra-contagious ebola, that it is unspeakable, unthinkable, and that even discussing it without a biohazard suit on will somehow create a wave of copycat suicides and an epidemic and therefore we should just zip our lips and praise the person who just “died” (not, never ever, “killed themselves”, even though that’s what actually happened) and ignore the gargantuan elephant busting down the walls of the room that the person in question just chose to publicly end their own lives as a statement. If the monks in Vietnam had lit themselves on fire in 2014, the bylines would just talk about their clinical depression and how it’s really sad we couldn’t have shipped more therapists into Vietnam along with our napalm, but gosh they did some good praying before they died.

I am really angry.*

*I know this is an emotion and it’s a strong one and also a negative one, and therefore I probably have several clinical things wrong with me that require pharmaceuticals to pacify me, but buckle up kids, because we’re going to talk about emotions like they are real.

Before Robin Williams killed himself earlier this week, I posted this on Facebook about roughly the same issue:

“Reading David Foster Wallace always makes me think deeply about what it means to be a person and the importance of imposing that question on daily life. Which I would imagine would be a legacy he’d be immensely proud to be known for. That said, it drives me utterly crazy that book jackets and flaps insist on the perversely simple ‘He died in 2008’ to explain his current absence from the world. It’s as though he were hit by a helicopter crossing the street or something equally hapless and mundane, not that he’d made a deliberate choice. I suspect he’d be equally bothered.”

-26 July 2014

And while a lot of people echoed the sentiment and agreed that there should be more open discussion of this, some people complained that suicide gets “fetishized” which seemed to me akin to the idea that we should censor the information of people’s suicides, its methods, any note or parting thoughts they left. And while I agree that some people are fascinated by suicide and its details for the wrong reason, the same is true about pretty much everything bad that ever happens in the world. But failing to talk about anything bad ever, while it may be the ultimate direction of our media, is not yet the norm, and of course stifles a conversation about, y’know, how to make things better.

Suicide is complicated. It’s icky, it makes people feel bad, and it is completely unrelatable for those who don’t experience suicidalism. I have to believe that the main reason suicide and its details are such a third-rail for so many is that it is so completely alien to the average person that they truly believe thinking about it or talking about it will give it to them, like ebola, and that something they find abhorrent and scary and awful will just infect them if they read about it or do anything other than say “blah blah blah I can’t hear you, please go talk to a professional”. But it is precisely this attitude about suicide and this shunting it off to the side that prevents the actually suicidal from feeling like they have a place to go or an outlet for talking about suicidalism the way they want to.

Indeed, this post from the Washington Post has been getting a lot of social media traction and includes the line “Suicide should never be presented as an option. That’s a formula for potential contagion,” attributed to Christine Moutier, chief medical officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) and, I promise, someone who has never wrestled personally with being suicidal. This line so fundamentally misunderstands the suicidal mentality that it would make your head spin, and does. For the suicidal, it is always an option. The issue is keeping it at bay long enough to delay it until the option doesn’t feel as wildly present anymore.

Like alcoholism, suicidalism is always present for the suicidal. You never get over it completely, it never fails to be an option. It’s just not something you want as much in the better times, something you can keep at bay. But no alcoholic ever thinks of a beer as not an option, much less does someone sharing “gosh, I want a beer” on social media constitute a clear and present danger to their sobriety. (If it does, they are completely and totally hosed in their efforts to stay sober in the United States of America.) And while I might personally say that a campaign to ban alcohol advertising everywhere to support alcoholics recovering would be a good step, no one else in the world would agree with me. It would be as ludicrous as Ms. Moutier’s statement should be considered.

True, not everyone, especially not vulnerable young teenagers first wrestling with the idea of being suicidal, has developed their strategies and coping mechanisms and ways to survive suicidalism. They are more vulnerable, susceptible, and prone to influence, like teenagers everywhere. But what kind of message does it send them to say that we shouldn’t talk about Robin Williams’ death as a suicide, shouldn’t mention how he did it, shouldn’t even deal with anything other than his wonderful career and “mental health issues”? Which, I’m sorry, but is a codeword for Feelings Which Shall Not Be Named. It’s a way of saying the only person you should ever begin to discuss your extreme feelings with is your therapist, because only they have the proper biohazard suit to deal with this ebola you are suffering from.

Yeah, that sounds like a really reassuring recipe for scared and vulnerable young teens wrestling with suicidalism. You have your hour a week with a trained professional to discuss those feelings. Otherwise, your feelings are invisible to us, kind of scary, and will be ignored even though it’s obvious they are impacting prominent people in our society in a profound way.

It would be like displaying the 9/11 footage and talking about United and American’s great track-record of safety and that anyone with concerns about how the planes came to end up in the buildings should discuss it with a local building engineer of their choosing. Anything else might inspire other people to crash planes into buildings!

When I was working at Rutgers, I would discuss the nature of suicidal feelings with some students struggling with same. I was later admonished against this by the administration that was trying to use some controversial aspects of my coaching as a way of ending the debate program that they felt was not a good use of money, as supported by the betrayal of my Assistant Coach at the time. One of the many reasons that I decided to quit my job was that it was very hard to imagine how I could continue to do it effectively without being able to discuss emotions and feelings and sometimes, yes, even suicidal thoughts, with the students who I’d spend forty to sixty hours a week working with. The attitude of the university and its official policy was that such thoughts and feelings were to be immediately referred to crisis staff, whose only role was to whisk the students off campus and into seclusion fast enough so that they would not become a negative statistic for the university. There has been a lot of public discussion lately about how university policies around suicide are actually encouraging and promoting the feeling of life-collapse for those already vulnerable to harming themselves. That somehow removing someone from their support and community, calling them a failure, and telling them to stay away until they get better is exactly the recipe for getting someone already suicidal to be even more serious about that effort. But universities, as a general rule, don’t institutionally care about these people and their ultimate fate. They care about liability and responsibility and our society says that no one can blame them if it didn’t happen “on their watch”, even if they were entirely the precipitating cause of an eventual suicide.

But something that I would discuss with people included my own personal strategies for surviving 24 years and counting as a suicidal person. I don’t know if these things are taught by therapists or not because I’ve never seen one, primarily in the last few years for fear of being locked up, shocked, and/or medicated against my will. Unfortunately our society sees these outcomes as ultimately best and once that ball starts rolling, it’s impossible to stop if you took the first step of your own free will. And sorry, but my free will is more important to me than being deemed “healthy” by a jury of this society’s standards.

Here are things they don’t discuss in these prissy little articles telling you to say that Robin Williams merely “died” and it was “unfortunate”:

1. You are more vulnerable to an impulsive suicide than a planned one. Planning takes time and effort. Set the bar and standards high for your suicide so that it will take longer to plan and you will have more time to talk yourself out of it. Don’t settle for something quick and mundane, no matter how much you’re hurting. When you are suicidal, you are also depressed and exhausted, have low energy, and the effort of doing something elaborate will be overwhelming and you will sleep instead and tomorrow might be better.

2. Hide your knives. Hide the utensils if necessary. Don’t leave anything dangerous lying around. You will of course know where you hid these things, but those extra few seconds of rummaging may be life-saving and critical. Again, it takes effort, which you tend not to have the energy for in the worst times. Put as many little barriers between yourself and something impulsive as possible. Stay back from ledges. Do not stand on the edge of train platforms, even when you’re doing better.

3. Set a very high bar for your suicide note. It is the last thing you will ever leave on this planet. It must be the best thing ever. It must say everything possible to everyone. Does this seem hard? Does this require a lot of planning? Might it not be better to deliver some of these messages in person? Good, wait till tomorrow and go talk to those people, tell them what you have to say in person. Keep revising the note. It’s not really perfect yet, is it? Maybe next week.

4. Take risks. Big ones. Keep in mind that suicide will prevent all of your other options, ever. If you’re willing to go there, you should be willing to do everything short of that. This includes running away, disappearing, renaming yourself, taking out all of your savings, if applicable, (or debt if not) and going on the trip you always dreamed of. If you’re really that suicidal, start treating yourself like a terminal cancer patient. Get all you can out of the next few days and weeks. You’ll probably find something fun or enjoyable or livable or good in there. Give yourself a chance to be happy after all you’ve been through. Even if it’s just for a few days. You’ll be glad you did, even if you ultimately make the same choice, but odds are that it will lead you down a different path that’s more livable.

5. It is okay to be sad. Everyone is sad. If you are not sad in this world the way it is structured, you are a nincompoop. This does not mean there isn’t joy in the world, or elation, or things to look forward to. But the people who aren’t sad, frankly, aren’t paying attention. Look at how people treat each other. Look at the wars and the famines and the plagues and the poverty. Look at it! But here’s the thing. You can’t just stew in your room about these things. Go talk to someone about it. If they just don’t want to go there and think about sad things, who needs them? Find someone who can take it. Everyone is truly sad about these things and the ones who aren’t are just in denial. Sadness does not mean you have a fucking disease. It means you have your eyes open in a place with real horror in it every day. But the horror only continues if everyone who sees the horror leaves. Your ability to actually see it gives you an obligation to do something about it to make it better. If everyone did that, the world would have wayyy less horror. So go talk to someone about it. Even if you have zero energy to do anything about it right now, talking to someone and feeling that sadness together will make you both feel a little less alone.

6. What do you like? Is there a new thing of that coming out soon? Books, movies, video games? I bet you can’t really wait till the next big one of those comes out. Wouldn’t it be sad if that were the best thing ever and you missed it? I know it’s a long painful time to wait. Why don’t you spend all of your time before then reading/watching movies/playing video games? Yes, all of it. All of it. You could! If you’re not going to live at all, if you’re really willing to go there, shouldn’t you be willing to just do the one thing you enjoy doing 100% of the time first? It beats the crap out of dying.

7. What if your best friend/mother/favorite celebrity killed themselves? Wouldn’t you feel awful about that? Wouldn’t you feel personally rejected and like there must have been something you could have done to help? Now, do you really want to put your loved ones through that? Really and truly? Even if you think some of them deserve that, do all of them? Even if you think no one in the world cares about you at all, is that really true? Really? Find the one person who might be an exception and tell them how you’re feeling and how much you need them. If you don’t, they will spend the rest of their life wishing that you had and that will be on you that you made them feel that way.

Now, many of these may not work for you. I’m sure some of them sound trite or trivial or stupid. But every single one of the above strategies has prevented me from killing myself at least once in the last 24 years. Every one. And in case you don’t think I have enough cred in this department since it’s been 24 years since I made a serious effort, I’ll tell you a little story. Last fall, under immense suffering and a confluence of seemingly ruinous events, I banged my head into a plaster wall, hard, eight times in a row. It was the back of my head, sure, because I was hedging a little, but I gave myself a concussion and have had floaters in both eyes since about a month after the incident. There’s a particularly bad one in my right eye that gives me more headaches than I used to have, especially when I read a lot, one of the things I truly love doing.

I get mad at myself every day for doing this, especially when the floaters are really prominent (there are better days and worse days). And it fuels my anger-spiral and my self-hate and all the things I wrestle with. These things are not a fucking disease, but they are the realities of living on this planet and having feelings and experiences that are not always cheery. Robin Williams did not have a disease, he was a person, complicated, feeling, compassionate, with a deep understanding and fear of the human condition.

And maybe if he’d lived in a society that made it more okay to talk about those things, to reach out to others (not just “professional experts”), one that didn’t shun and shunt suicidalism off to the corner and call depression ebola, he’d still be with us today. Your silencing of this discussion is killing people. And it’s not okay.

My floaters have given me another little strategy, another thing to be upset about. Even though they’ve diminished my quality of life, they are a reminder that acting on my suicidal feelings does harm to me and that I’d rather live most days without harm. So it’s made the consequences a little more real. And that’s a good reminder.

Every time a celebrity kills themselves, it’s a little totem of the same thing. It’s a reminder that we need to talk about feelings and emotions and the state of our world and work to improve all of them. Not in our biohazard suits, but raw, openly, laid bare, with all our thoughts, feelings, and real experiences on the table. If we were all just real and open and honest with each other about our darkest hours, we’d all realize how un-alone we truly are.